“La mayoría de la gente es incapaz de acomodar su atención al vidrio y transparencia que es la obra de arte: en vez de esto, pasa al través de ella sin fijarse y a revolcarse apasionadamente en la realidad humana que en la obra está aludida”.1

La deshumanización del arte. José Ortega y Gaset (1925)

- 2.1 Measuring news media

- 2.2 Measuring social media

- 2.3 Measuring public opinion

- 2.4 Agenda setting

- 2.5 Summary of findings

News and social media construct reality, or at least the reality we as a society know, and contribute to shaping people’s opinions. The world we know is what we see and learn through the media; news media are the lens through which we see reality. As Ortega y Gasset puts it regarding art, people tend to see news as the reality instead of understanding that news media offer a curated, filtered, and biased view of what happens in the world (Ortega y Gasset, 1925). It cannot be otherwise. Real-world facts have to be selected to offer the public an affordable amount of information, in terms of number/quantity, to understand what is happening out there, unless we pretend to know everything that happens, which is not humanly possible2.

Many metaphors have been used to explain the difference between real-world facts and what is printed or narrated. Lippmann (1922) (cited in McCombs (2004) p. 3), around the same time as Ortega y Gasset, used, for example, Plato’s Allegory of the Cave: “how indirectly we know the environment in which nevertheless we live, but that whatever we believe to be a true picture, we treat as if it were the environment itself”. In Ortega y Gasset’s analogy, the shadows would be the news of a projected reality that is “out of sight, out of mind”, as Lippmann put it (Lippmann, 1922), in its chapter “The World Outside and the Pictures in Our Heads”. Lippmann’s much cited book set the basis for the development of agenda-setting theory five decades later with McCombs & Shaw’s (1972) article.

Most of the time, readers of newspapers or watchers of television news broadcasts are not able to differentiate what really happened from what they were told happened. It is not possible to distinguish between the event and the constructed mediated event; they are one and the same thing in our minds. As Luhman (2000, p. 1) puts it3 “Whatever we know about our society, or indeed about the world in which we live, we know through the mass media.”

This research is focused on how the transfer of the selection of issues and stories from the news and social media agenda influences the public agenda. The main channels of the mass media ecosystem, their characteristics, and how they interact with each other are analyzed with new tools to provide a more accurate picture of how they work. Related communication theories such as intermedia agenda-setting, second-level agenda-setting (attributes), third-level agenda-setting (network of issues), and framing are also revised.

This chapter examines these theories and existing literature and reviews various approaches to measure news media and social media channels. Each news and social media channel of interest is analyzed to extract their unique characteristics and how they are studied. Social media are analyzed separately from the rest of the news media channels in the 2.3 Measuring social media section, to address their particularities. In the databases presentation (chapter 8), Twitter is not analyzed independently, and its analysis is integrated as one more mass media channel.

2.1 Measuring news media #

To measure is one way of performing an analysis. “What gets counted counts”, claim Klein and D’Ignazio, citing the geographer Joni Seager (D’Ignazio & Klein, 2020). Similarly, measuring news coverage enables us to analyze and understand how news media work beyond the subjective (or preconceived) picture people build in their minds.

In the 16th-17th centuries in the West, news media consisted of what came to be known as newspapers (broadsheets, pamphlets, booklets). Information was printed, and when scholars got interested in “measuring information” centuries later, this equaled, in its most basic form, counting the number of news. Those looking for more accurate metrics could measure the length of the articles to get a more nuanced sense of what news media considered important. In the 20th century, with the introduction of new forms of mass communication, like radio and television, and more recently with the World Wide Web in the 1990s (with the 24 hour cycles of information flows), and the multiplication of new news media outlets4, it is, simply put, no longer possible to count news: It is not longer possible to get copies of several newspapers and count news stories.

The problem of measuring news media coverage in the digital era is related to the multiplicity of channels and the vast amount of data needed to gather the current media ecosystem. As said in the introduction to this chapter, to measure is to select which aspects of reality are to be studied, and for digital objects, this is a key question. Whereas scholars had in the past to decide which media sources to gather (local and national newspapers, television, radio, or magazines), the technical characteristics of digital media do not allow such a “simple” analysis. Although a front page of a printed newspaper (or a picture of it), or even a video recording of a television news broadcast, are—to the eyes of the researcher—similar in that they contain in themselves the information the researcher needs5, the content and look of a home page of an online news site in a given moment depends on the device where it is displayed or the user’s cookies, to name just a few key modifying characteristics. Home pages, as digital artifacts, are written on HTML, JavaScript, and CSS code that calls images, videos, and audio files, and it is not clear how they need to be preserved as images or video files.

With the availability of tools to gather and store information or publicly accessible news online archives (like those for television news or websites at archive.org), it is now possible to get more information than ever and automatize its processing. However, contrary to the general belief, not everything published is or can be archived, and not all the analysis can be automatized. Long-standing forms of publication such as printed newspapers are systematically archived, whereas others such as TV, radio, or websites have not yet consolidated archiving methods and established analysis methodologies. This situation makes the analyzing the current media ecosystem more complicated and fragile because it depends on the live gathering of published news. Otherwise, they would be forever lost for the analysis6.

While front pages of newspapers are unique and immutable daily pieces of information that condense the main stories and issues of the day, home pages of news sites are fluid, continuously updated spaces where news stories move during the day. Until recently, researchers have counted articles or surface area or news stories on front pages, generally using the total number of articles published by the news outlet instead of the selected articles on the front page. It is usually a question of the availability of the sources, and many researchers depend on existing archives of news stories to make their analysis.

Each news channel has its characteristics and needs to be properly archived. Some archiving methods are more than a century old, like e.g. those designed for printed daily newspapers, while others (TV) started in the 1960s; others like online news are even more recent. The news media channels, and the elements within those channels, analyzed in this research, are the following:

- Newspaper front pages (Sec. 2.1.1)

- Home pages of online newspapers (Sec. 2.1.2)

- Television Newscasts (Sec. 2.1.3)

2.1.1 Newspaper front pages #

This section draws extensively from the article in collaboration with Sasha Costanza-Chock PageOneX: New Approaches to Newspaper Front Page Analysis (Costanza-Chock & Rey-Mazón, 2016).

The front page is the most disputed/contested space in printed newspapers. Journalists want their news to be on the front page to acknowledge their work. The selection of front page news results from a careful process involving key players in the newsroom; the process must consider many circumstantial aspects such as newsworthiness, potential public interest, and past coverage. It sets the tone of the newspaper, and it is the piece of information that will be shared more broadly in other news media channels. It has been used extensively in numerous academic studies because of its availability and conciseness. The existing academic literature supports its use as a proxy to the entire media ecosystem, even in this digital era where some might expect a decline in its importance and impact. Front pages offer the possibility of time ‘freezing’ the ongoing and faster live coverage of events and allow other ways for interpreting news on another, more distant, historical level (Niemeyer, 2019)7.

Still relevant in the broader media ecosystem

Despite the spread of broadband internet and mobile devices, the rise in digital media literacies (Anderson et al., 2011), and the growth of social media use8, printed newspapers continue to have a significant role in organizing public and elite agendas (Costanza-Chock & Rey-Mazón, 2016). Traditional printed newspapers retain a great influence across the entire media ecosystem, even when circulation is declining in many countries, which indicates that their impact goes beyond direct readership.

Golan (2006) and Danielian & Reese (2012) analyzed intermedia agenda-setting relationships. They found that newspapers, magazines, and television newscasts tend to give a similar amount of space and time to stories and demonstrated The News York Time’s agenda-setting role, especially for television news. McCombs (2004) found that the appearance of stories on the front page of The New York Times can frequently legitimate a topic newsworthy; to some extent, it can be considered that appearing on page one of the New York Times is the news itself: “I made it to the front page of the NYT”. Boyle (2001) also demonstrated that printed newspapers had a strong agenda-setting effect on TV networks, in the same way that McCombs et al. (2000) found that newspapers influenced the agendas of TV and radio broadcasts. Breed (1955) demonstrated how large metropolitan newspapers influenced the agenda of smaller local newspapers. Newspaper coverage also plays an important agenda-setting role for blogs and social media.

Front pages of daily newspapers are still powerful indicators of the prominence provided to a given news story and drivers of attention to all the other media channels across the media ecosystem. They are displayed and commented on television and radio news programs. In the last television news programs of the day and early morning radio news broadcasts, they are used as an indicator of what other media outlets find relevant. At the same time, front pages are the subject of journalist analysis. The news selection and framing of other news media outlets are considered the news. The front page is an “historiographical source as it condenses and compresses the first significations, interpretations and narratives of what is happening. They appear, for example, in television newscasts or on websites that offer press reviews. Moreover, this re-use is not a new ‘digital’ phenomenon, but a common pattern in journalistic narratives” (Niemeyer, 2019, p. 3).

Communication and media scholars have studied the production of newspaper front pages, including how different social, cultural, political, economic, and interpersonal forces shape the editorial selection and prioritization of stories (Broder, 2000; Forrest, 1934; Gans, 1979). Given the well-known influence of this selection of news on the entire media ecosystem, newspaper editors dedicate time and resources to deciding what to highlight (Sumpter, 2000).

The front page is also a highly contested political space. For example, Álvarez-Peralta (2011) argues that front page analysis provides a more direct lens on a newspaper’s editorial line than the newspaper’s editorials. He notes that editorials are carefully constructed, public-facing documents that frame the opinions of the newspaper editors for a critical reading public. In contrast, analysis of the content and framing of front page stories provides access to the paper’s ‘hidden’ editorial stance (Álvarez-Peralta, 2015). Similarly, Reisner (1992) explains how newspaper editors select the stories that are more aligned with their ideological preferences9.

From column inches to percentage

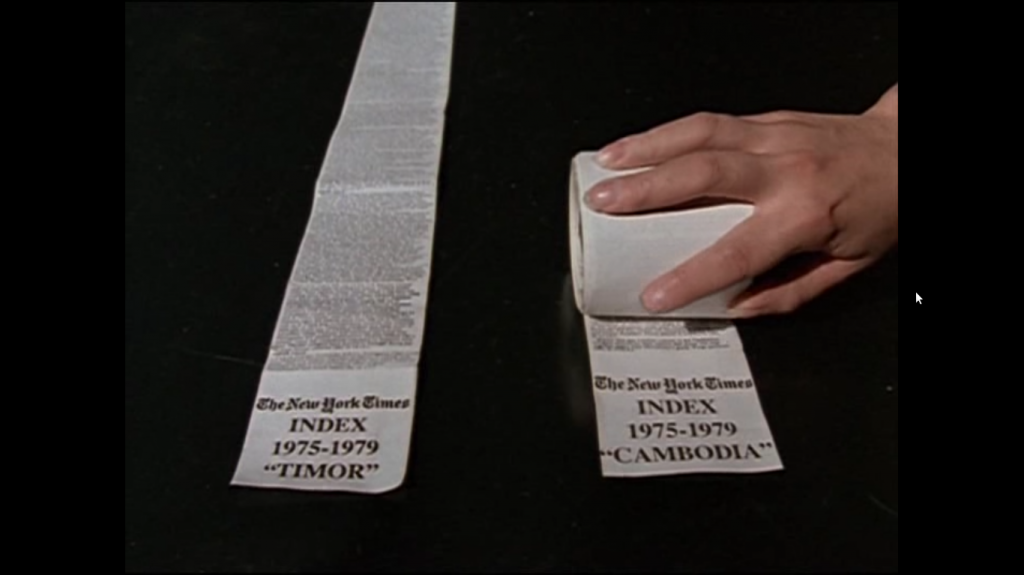

The most basic measure to track news coverage is to count the amount of news, but more nuanced metrics such as surface area or percentage amount the total amount of news are also possible. In the 1980s, column-inch measurements gained great visibility thanks to the popularity of Manufacturing Consent (Herman & Chomsky, 1988), although already measuring surface area was not a new approach by then (Fig. 22). As early as 1928, Yeuell used it to measure the relative amount of space dedicated to different topics, employing column inches as the unit of measure: “a column inch is an item of news one inch long and the width of a column” (Yeuell, 1928, p. 92). To follow this methodology, researchers needed physical copies of the newspapers to measure the space devoted to specific topics or stories and input the measurements into a spreadsheet by hand. Yeuell not only measured the surface area dedicated by category, which provides a more detailed measure than the number of articles but also published the percentage of coverage dedicated to each category. This methodology made possible the comparison between different newspaper sizes and formats.

Herman and Chomsky used column-inch and other quantitative metrics like number of articles, number of front page articles, and number of editorials to provide empirical support for the ‘propaganda model’ of the news system. Content analysis techniques for news communication evolved and incorporated systematized coding instructions and intercoder reliability measures.

McLeod et al. (1974) calculated the total coverage by measuring the column inches (including headlines and pictures) on the front page, jump page, and in the editorial for six selected news items, also calculating the relative percentage of space dedicated to each of them. They showed that the ranking of the six issues they analyzed was essentially the same for both types of content. They also studied the adequacy of only using selected pages (front page, jump page) by comparing them with the total content of the newspaper to show that the sub-sampling did not reveal a critical revision of the close attention to the six issues. However, it could overestimate the attention to the main categories analyzed (honesty and Vietnam). Kim and Chung (2017) used the relative size stories on the front page to account for the different page sizes to compare The New York Times with six metropolitan national newspapers.

Communication scholars have developed studies that employ the number of articles on front pages. Boydstun (2006) categorized all The New York Times front page news stories for the 1998-2006 years based on a codebook developed by the Policy Agendas Project10. Wolfe et al. (2009) used Boydstun’s dataset and compared it with the full content of the newspaper and found that front page and full-paper coverage have significant differences, e.g., many elements that appear inside the paper may rarely or never appear on page one. Front pages cover different issues and fewer topics (less entropy, narrower scope) than the entire paper, although they note a strong positive correlation (r=+0.78) between front page coverage and full paper coverage of any given topic. Front pages are more event-driven and have a higher entry barrier that only allows “hot topics” to be displayed there. The full-paper analysis is needed to analyze less trending topics. The coverage of issues on the front page is more likely to repeat the previous day’s coverage (higher ‘friction’). Using the same methodology, Chaqués-Bonafont et al. (2015) categorized every news story on the front pages of the two leading Spanish daily newspapers (1996-2011) that is used in one of the case studies of the present dissertation.

Di Tella & Franceschelli (2011) used the percentage of surface area dedicated to corruption scandals involving members of the national administration on the front pages of the four main newspapers in Argentina (1998-2007). Then, they compared the relative amount of coverage to government advertising in those newspapers and found a negative correlation. More government-paid advertising correlated with less corruption coverage in these news outlets, consistent with provincial officials’ reporting.

In their research using front pages of The New York Times to study network agenda setting, Saldaña and Ardèvol-Abreu (2016) used the Proquest Historical Newspapers database to search for all the stories that mentioned drugs in headlines, leads, or captions. They used the front page stories on the month before the Gallup poll to find out that there were agenda-setting effects according to the “network agenda-setting model” that considers the relation of the attributes and not only the amount of news coverage or percentage of answers.

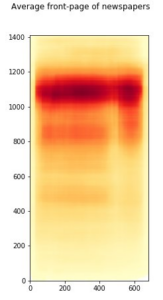

Massive analysis of front pages has also been done using machine learning for automated analysis. Sam Zhang, for example, has automated the analysis of newspaper front pages archived as PDF documents (https://github.com/samzhang111/frontpages). His software can detect news boundary boxes and parse text to create heatmaps of front pages related to a search query.

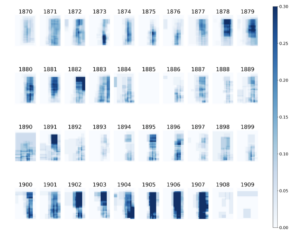

Germain Lee et al. (2021) used machine learning to analyze the visual layouts of multi-ethnic newspapers from the late 19th and early 20th century in the US from the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America archive instead of focusing on individual pieces of textual and visual content.

Figure 23: Location of news heatmap. From Sam Zhang.

Theory gaps and contributions

In the database section (7.5 Databases), I present Pageonex, the software developed to aid the coding, analysis, and visualization of newspaper front pages used in the present research and described in a previous article (Costanza-Chock & Rey-Mazón, 2016). This novel methodology automates parts of the analysis, simplifies others and enables to share the analysis online.

2.1.2 Home pages of online newspapers #

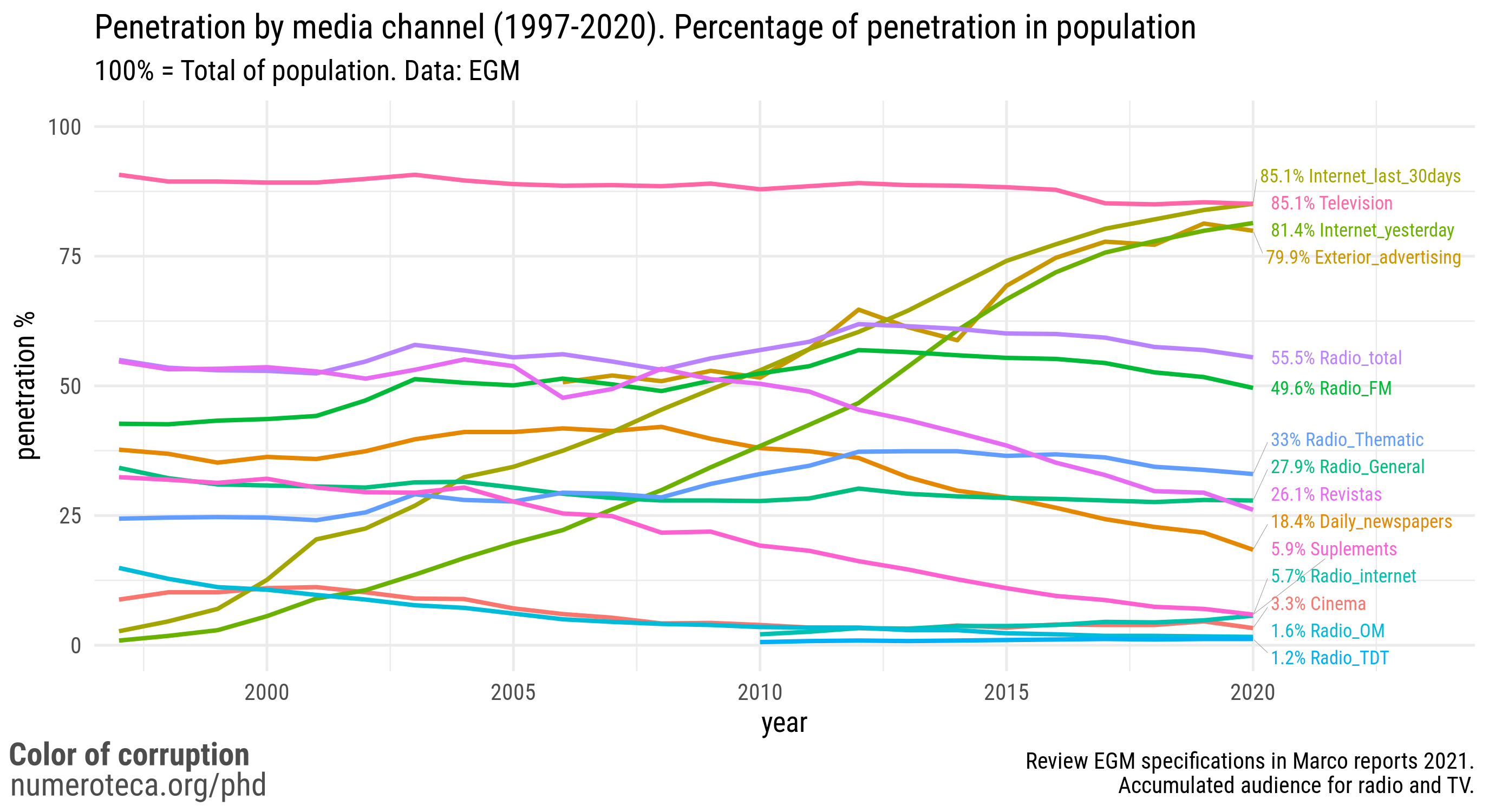

Research about online news sites, and particularly of their home pages, does not have such a long history (Li, 2013; Salaverría-Aliaga & Sancho, 2007), since it was not until the mid-1990s that many newspapers opened their first online versions of their printed version on the World Wide Web. Online news sites were static in the beginning and resembled their printed counterparts, but after some years, and thanks to a broader user base, they were converted into the current websites and principal media channels we know today, with penetration rates that match those of the television in countries like Spain, with 85.1% in 2020 (AIMC, 2021) for television and Internet use in the last 30 days. The rate of use seems to be arriving at its peak.

Since more than a decade ago, online news can now be characterized by its immediacy and interactivity (Karlsson & Strömbäck, 2010). Digital media are interactive because they allow more interaction of users than offline media and immediate. After all, the news cycle has been radically shortened (Singer, 2003). Karlsson and Strömbäck also noted the lack of research into news stories and that most of the analysis was conducted at the web site-level. Newsrooms need to publish news as quickly as possible and keep updating and revising content even once the public’s attention and visits have faded. Traditional research methods of content analysis face new problems in this rapidly changing environment and might be one reason for the scarcity of such analysis for this type of content (Gerd G. Kopper et al., 2000). The premise of content analysis relayed on the notion that content existed, was finished, and would be studied. However, this assumption is challenged by the current media ecosystem, where there are continuous edits (Deuze, 2008) in the news stories’ headlines and copy text.

Like printed front pages, home pages are highly contested spaces. If journalists and their news stories compete to make it to page one (Reisner, 1992), there is a similar struggle to make it to the top news stories on the home page. The selection of news on the home page also reveals the editorial choices of the news media. Digital space is also limited, and not all the news can fit, so the same battle to reach the front page arises.

With the emergence of social media, home pages might have lost some of their traffic, but they are still critical pieces of information, where media outlets select their most relevant information and contribute to redirecting substantial traffic to certain news stories by giving them prominence. At the same time, the home page is not the only way people can use to arrive to news stories since now people can (and do) use “side doors”, like Twitter or Facebook, to use Kirkland’s (2014) words.

In recent years, with the emergence of paywalls, where users cannot read articles unless they pay a monthly or daily fee or have an account, or in some cases, can only read a limited amount of articles per month, images, and headlines (and subheads) in the home pages are the only pieces of information non-subscribers can access. This behavior resembles the experience of the quick view that readers experimented with printed front pages when they glanced above the fold news in a newspaper kiosk. A quick view of the top news of multiple home pages might be a way to get a broad picture of what media outlets are selecting as important to try to understand the news media agenda.

In 2014, an internal leaked report on digital innovation from The New York Times (Abbruzzese, 2014; Benton, 2014) reflected on the way the digital media environment has changed the media ecosystem:

“Each night, we printed our best work. Then we loaded it onto trucks to drive it to cities and towns. Then we enlisted kids to bike from house to house to deliver our papers to readers’ doorsteps. For non-subscribers, we dropped off bundles of papers at corner stores and newspaper racks, and painstakingly tracked sales to see where more copies were needed.

“Report on digital innovation”. The New York Times. 2014 (Abbruzzese, 2014)

We take this work for granted now, but our home delivery and single-sales efforts represented one of the most sophisticated consumer-outreach operations in history. But when the time came to put our journalism on the web, we adopted a much more passive approach. We published stories on our home page and assumed that most people would come to us”.

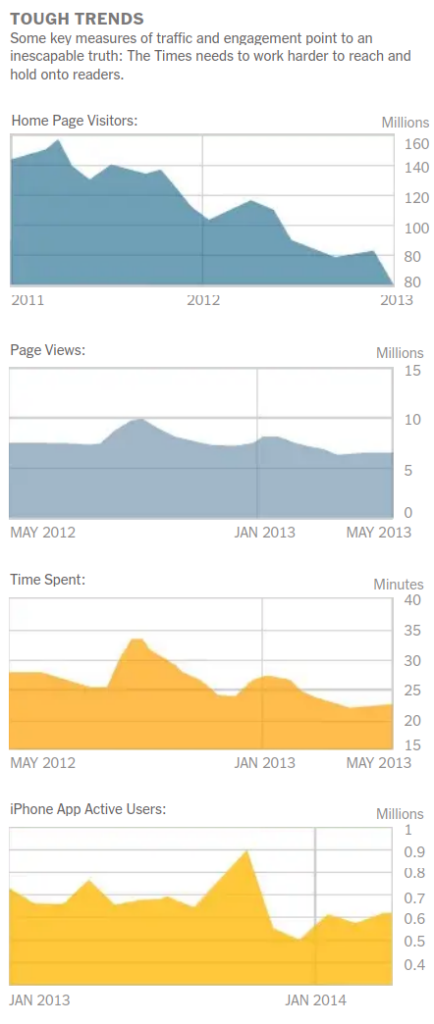

The report analyzed, among other vital issues, the change in the use of the home page, stating that visits to the home page had fallen 50 percent in the period 2011-2013, and also referring to the need to reorganize the newsroom from a “print-first” to a “digital-first” strategy.

This report made some journalists certify the death of the homepage, or at least a change in how home pages were traditionally conceived (Kirkland, 2014). For these two years, 2011-2013, the page views remained fairly steady at their website, so the loss of visits to the homepage was related to the way visitors accessed their site, which might indicate a growth of visits via social media. The website still had 80 million monthly visits, nevertheless. The home page had been, until then, their main “tool for getting our journalism to readers, but its impact is waning. Only a third of our readers ever visit it”, the report stated. Kirkland (2014) stated that news outlets were trying to find ways to retain readers after visiting an article page by creating homepage-like sections at the bottom of their stories. Other strategies involved the creation of an infinite scroll of stories.

In conclusion, homepages in online news sites are less influential than before the emergence of Facebook and Twitter, but they are still relevant in the way they drive attention, which justifies the time and resources spent on them by newsrooms.

Power users, in Kirkland’s words, or “influencers” to use a more popular term, i.e., those who select the information and redistribute it on social media, also depend on the selection of news in the home pages or RSS feeds (Klein, 2014). These users might be a small elite group but can influence many, in the same way, elite/legacy media influence other smaller media.

Other community-based social news networking services such as Reddit in the USA, and meneame.net in Spain, also drive social media traffic to online news media. On these sites, users suggest URLs that other users can up-vote. The most popular stories are highlighted on the home page and can bring significant traffic to news stories that had otherwise passed unnoticed. News that get popular on these sites can be re-shared on social media and re-broadcast by news media, starting the sharing cycle again.

Bookmarking and URL-typing are other ways that people can use to arrive at news stories. People can have a news site bookmarked and visit it with a click. To access the news sites, people can reload an existing loaded home page, type the URL of the newspaper (using auto-complete features), click on a bookmark or search for the name of the newspaper in a popular search engine.

Home pages maintain the attractiveness of the curated selection of news on front pages. Readers find value in this careful selection of stories by each news outlet. A similar content selection to that of printed front pages (Álvarez-Peralta, 2015; Reisner, 1992) is expected. The editorial decisions of both media pieces, online and printed, emerge from the same newsroom, though with different characteristics. When studying homepages, other variables will come into play, like live decisions by web editors to change the news position or wording of headlines, depending on live coverage events, availability of information, web statistics11 –low or high traffic that news stories receive– or how news stories are being shared in the social media sphere/networks.

The existing literature has adopted the 24/7 news cycle to describe/name the current constant fluid news media dynamics (Lin & Atkin, 2014; Rosenberg & Feldman, 2008). News sites are continuously available. Readers can visit them when they want. International/worldwide cable news or wire services are also continuously available and provide constant news feeds. News television channels broadcast 24/7, but many newsrooms are not always available. Only very big news outlets have editorial teams that are truly operative 24 hours a day.

Results of the present research show how home pages are edited continuously every hour, but there are usually massive replacements of articles on the home page once or twice a day. Results also show periods where the page remains almost static, i.e., without almost no updates during certain times, in particular at night (see Sec. 10.4).

Freezing the moment

The academic literature also examined capturing and analyzing digital content. This type of research involves gathering and analyzing news sites and has to face the rapidly changing environment of digital technologies and user interfaces, and the vast amount of data that can be potentially stored. News sites, either single news stories or home pages, can be captured in many formats and methods: image screenshots, PDF, RSS feed, and automated downloading. All of these methods have the common problem that they unavoidably simplify the original digital object (Karlsson & Strömbäck, 2010), so depending on the objective of the research, a different method should be employed and the sampling rate adjusted.

Websites use HTML language (Hypertext Markup Language), the standard markup language employed to display documents in web browsers in the World Wide Wide. The HTML code, and other technologies such as JavaScript and CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) form what users see when visiting a website on their browsers or mobile apps.

Different automated projects have been devoted to capturing the fluid ecosystem of online news. The discontinued NewsDiffs initiative (http://newsdiffs.org) tracked online news changes over time to build a publicly accessible dataset of changes/edits in news stories. The Wayback Machine project (https://web.archive.org) of the Internet Archive is a digital archive that preserves archive copies of web pages, including many news sites ones. All of them face the same challenge regarding the sampling rate.

Coche (2015) used content analysis of the home sites of the top 2 news sites in four countries to study the gender gap in sports news coverage. Her manual analysis involved sampling days and times, collecting the home pages in 6-hour cycles (4 per day) on the selected dates and saving them in three formats: Apple’s web archive, HTML, and PDF, using the software Web Snapper. This method resulted in 448 home pages archived and coded (2,930 news classified).

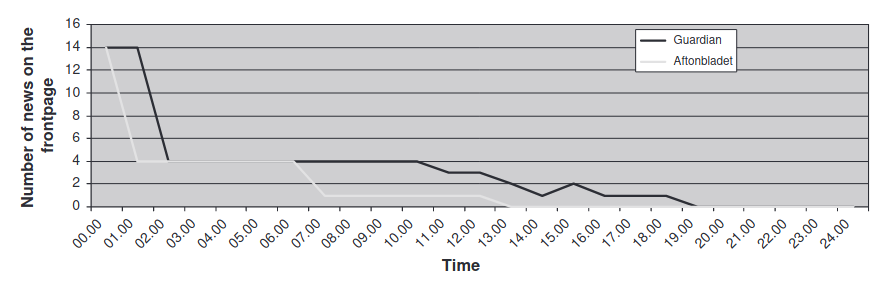

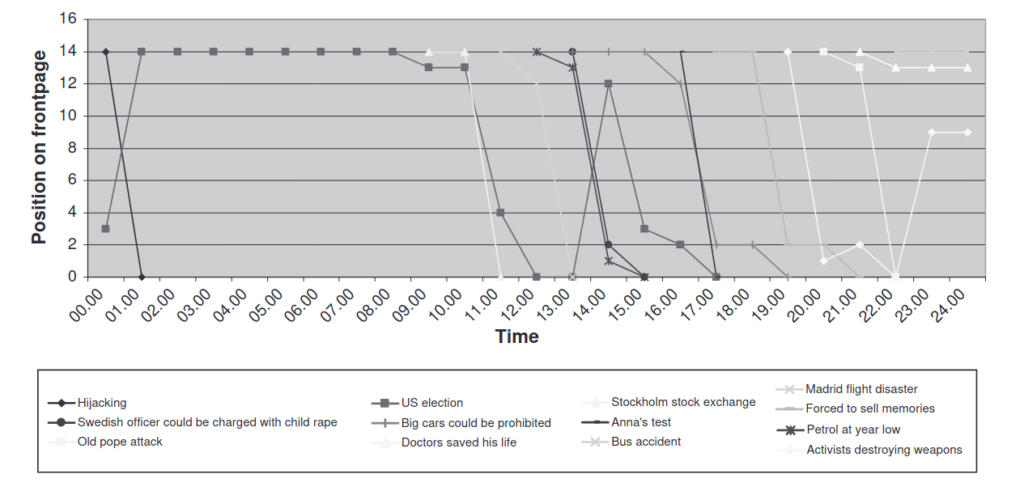

Karlsson & Strömbäck (2010) studied different methodologies to “freeze” the fluid digital news flow on websites. They analyzed how long the top 14 stories remained on the home page during one single day news cycle on two news sites. Their limited analysis showed that in 19 hours, all the news stories were gone from the front page. They could track the drop of the selected stories at 1-2 a.m., likely related to the refreshment of the entire home page. The selection of the top 14 stories is related to the number of top stories Guardian.co.uk had at the time. They also followed the position of the top stories, i.e., those that were the “top 1” on the front pages, represented on the following data visualizations:

Home page, which home page? Limitations

Whereas front pages are unique objects12, home pages have many more formats depending on the location of the user, their customization features (automatic and non-automatic based on the user), user device13 (smartphone, tablet, desktop, and tablet), or if the visit is from the website or via a mobile application. This situation makes home page analysis more complex than that of paper copies. Some users could see stories as full-width pictures and leading text, while others accessing from mobile devices could only read a selection of the content with smaller images.

New native digital media, like Quartz or Medium, and now also legacy media, convert every article into a mini homepage, i.e., every article page has links and references to other relevant articles (Klein, 2014), to offer the reader more articles and sections and to try to keep the user in the website. Some news sites offer an infinite scroll14.

Theory gaps and contributions

The study of news sites home pages still presents challenges that need to be tackled. Most of the methodologies do not analyze the constant flow of news articles and its possible implication in the way readers receive the news. I present in Sec. 7.5 and in the Annex, Homepagex, a software and the method developed to overcome this for the present research. This novel method follows the position of the news items on the home page on various days to have a complete picture of news flows and news cycles on websites. The methodology combines database building features (web scraping the home pages hourly) and automated content analysis.

2.1.3 Television Newscasts #

“But if we briefly consider the natural history of most issues, the larger capacity of daily newspapers relative to television news means that audiences often have longer period of time to lean the newspaper agenda. Television news is more like the front section of the newspaper.”

(M. McCombs, 2004, p. 49).

Television newscasts have been used in communication studies as a proxy for the television agenda. By analyzing video recordings, abstracts, or subtitles (Althaus et al., 2002), scholars have researched news stories on television. In the US, archives like the Vanderbilt Television News archive, Lexis-Nexis, or the open access Internet Archive TV News (https://archive.org/details/tv) are based on captions or subtitles, which make newscasts searchable, and in some cases, watchable. Television channels in the USA are obliged to publish their content with captions, so those captions can be used to archive the videos and make them searchable. In Spain, the Fundación Ciudadana Civio (2022) has recently published a dataset of television newscasts of the public-service broadcast television network in Spain (RTVE) called Verba, which has allowed television analysis on public television (Arévalo Salinas et al., 2021).

Generally speaking, television channels show a mix of programs in which newscasts are included. Two or three times a day, news programs condense the news agenda in 30-60 minutes. Like the limited space of the front pages, on-air time is here highly contested, and only a few news can be included. News programs usually start with a summary that highlights what will be broadcast and that can be eventually used to detect the selection of the selected issues so that it can be considered the front page of the most important news items of the newscast. Time dedicated to a story and its position in the total ranking of news are indicators of its salience. Measuring TV news is, therefore, a question of counting the number of news stories, length and position within the news program.

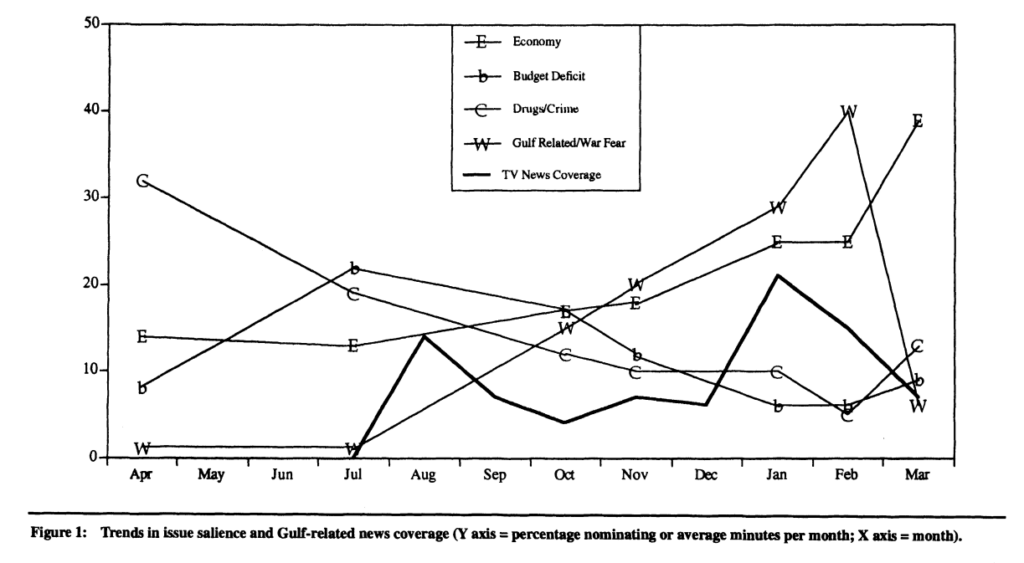

Iyengar & Simon (1993) used the relative duration of news stories in television newscasts to analyze news coverage about the Gulf war on ABC network: “the average amount of Gulf-related coverage per month was then calculated by summing the total number of minutes from that month’s sampled broadcasts and dividing by the number of reports sampled. The proportion of news coverage allocated to the Gulf was determined by dividing the coverage of the Gulf by all coverage” (p. 371) (Fig. 13).

Hester & Gibson (2003) studied the second level agenda setting (attributes) about economic news using ABC World News Tonight broadcasts and the front page of The New York Times (1998-2002). The television newscasts and front-page stories to conduct the analysis were selected using a search word query in the Lexis-Nexis database and then coded manually according to favorable or unfavorable framing.

Watt et al. (1993) studied network news coverage coded from daily entries in the Television Index and Abstracts from the Vanderbilt Television News Archives. Each story was coded for prominence features: the amount of time devoted to the story, whether film or videotape footage was shown, time placement within the broadcast, and the identifying sentence describing the story content. They used a prominence formula adapted from Watt and can der Berg (1981):

Prominence: = (TPT – TNS) / TPT + DS / 150 + FF

where TPT is the total news program time (1,800 seconds), TNS is the time from the beginning of the story (in seconds), DSthe duration of the story (in seconds divided by 150, the typical length of a news story), FF the presence (0.5) or absence (0) of a film or video. Longer stories that appear nearer the beginning of the newscast, and use video footage, will have higher prominence scores.

Theory gaps and contributions

The analysis of television newscasts still has a lot of room for improvement, particularly the non-aggregated analysis (day to day) and its visual representation. In section 7.5, I present in VerbaR, the methodology I have developed to analyze TV newscasts visually, using the position of the sentences that match a certain word query. It uses Verba, the novel database of subtitles developed by Fundación Ciudadana Civio (2022).

2.2 Measuring social media #

Social networking sites are changing the current mass media landscape. The use of social media (also “social networks”), with the expansion of mobile devices and broadband Internet, has enabled the direct participation of citizens in the hyper-connected media ecosystem. Following boyd and Ellison, they are used in the present research as the “web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system” (boyd & Ellison, 2007, p. 211).

As happened with the emergence of alternative media, like the surge of blogs in the early 2000s (Kelly, 2008), social networking platforms like Facebook and Twitter—to cite the most popular—have become relevant tools that drive an substantial amount of the Internet traffic and people’s attention. Compared to traditional news media consumption, social media users are no longer mere consumers but potential producers or re-distributors of stories and ideas. They are part of the new reader-writer culture and contribute to disseminating news and participate directly in the creation, selection, and framing of the stories, thus modifying the agenda-setting traditionally dominated by the mainstream media (Negroponte, 1996; Shirky, 2008; Sunstein, 2001).

Accordingly, analysis of social media messages has become a way to measure how social and political reality is constructed and framed. Following the emergence of blogs, scholars have used the content and relationships among users in social channels to analyze the role social media networks play in the media ecosystem.

Current social networking platforms can be classified according to the primary way they are meant to be used: they can be networking sites developed to connect people; media sharing platforms to share images, videos and texts; discussion platforms more focused on the conversation; book marking sites to help users organize and share URL; blogging platforms. This classification, however, offers only a simplified picture of the actual situation because each network evolves with time, resulting in a hybridization of features that make them share characteristics and features and become more similar. For example, a platform centered on short messages, like Twitter in the beginning, currently accepts the publication of images and videos15.

2.2.1 Measuring Twitter

Twitter is presented here separately from the other news media channels because of its special characteristics, but, in the database section 7.5, it is presented as one more mass media channel.

Twitter is a micro-blogging online social networking service where users can post short messages known as “tweets”. Messages were originally restricted to 140 characters, a limit that was doubled to 280 in November 2017. Users can follow each other to obtain “retweets” (i.e. re-broadcast existing published messages), or like tweets published by other users. By default, all messages are public and accessible, but access to them can be restricted by a user, making her account become private. Since its creation in 2006, Twitter has become one of the most popular social media websites and networks where users exchange information.

With time, Twitter has evolved and shares characteristics with news media channels. It features news stories, and it can be understood as a kind of “home page” of the most important stories (trending topics); the timeline can be a true list of the tweets in chronological order (all tweets from users followed by another user), or a selection by an algorithm of the more relevant tweets according to the user’s profile. Individuals and news media users, both news media accounts and journalists, coexists on Twitter with politicians and public and private organizations and companies. The main difference with other news media channels is its multi-directionality: all accounts can publish and re-share other messages.

Twitter is the preferred place for researchers because its openness and accessibility allow them to get the data and directly measure how information propagates (Ye & Wu, 2010; Zhao et al., 2011). For Driscoll and Walker, “Twitter is particularly compelling because(…) [i]n comparison to Facebook”, basically closed to the academic community, “tweets are small in size, public by default, numerous, and topically diverse”. It allows researchers “[w]ith little more than a laptop, an Internet connection, and a few lines of scripting code, (…) [to] aggregate several million tweets in a short period of time using widely-available, low-cost tools” (Driscoll & Walker, 2014, p. 1746).

Researchers use Twitter as a window to society (Bruns & Stieglitz, 2014). As several scholars have noted, some problems limit the utility of this type of research. Driscoll & Walker (2014, p. 1746) point to three recurring problems: the lack of reliable and reproducible data collection, the way Twitter is a system that is constantly changing, and that “researchers lack a common vocabulary for describing tweets and the metadata that accompany them”. It is important to use consistent terminology to enable comparison across different studies (Bruns & Burgess, 2011a, 2011b, 2012; Congosto Martínez, 2016; Howison et al., 2011).

Driscoll & Walker (2014) compared the three publicly accessible APIs (Search, REST, and Streaming API) with the real-time stream of tweets provided by the Gnip PowerTrack commercial service (Walker et al., 2013). The results showed that the Streaming API was suitable for longitudinal (i.e. over a more extended period) data collection and not so much for high traffic events due to the 50 tweets per second limit of this method. For massive and short events González-Bailón et al. (2012) also found out that Search API results are not a random sample of overall Twitter activity. Currently, the endpoint of the full-archive search in Twitter API version 2 limits to 300 requests per 15-minute window16 (Twitter, 2022). As discussed in the methodology section, in this research, t-hoarder and twarc software are used for Twitter data acquisition because they help interact easily with the Twitter API.

The “user timeline”, i.e., the list of messages tweeted or retweeted by the accounts followed by a user, is the place where users can find messages, but (relevant) tweets can be viewed in other ways:

- Users can see tweets in their chronological timeline. When user A follows user B, it’s likely that user B tweet will be displayed in the infinite scroll to user A, including original tweets and retweets. The emphasis likely has two reasons: (1) users that follow many other accounts will not read everything that is published (all the tweets of the people they follow), and (2) Twitter does not display all tweets.

- Users can see tweets in their recommended timeline. Twitter displays tweets that might interest the user based on recent activity or predefined settings. Note that this is different from the chronological timeline above.

- Tweets can be found in the “trending topics” section or by reviewing tweets in hashtags.

- Tweets can also be searched.

- Tweets are linked or embedded in other websites or social networking platforms.

This review about Twitter analysis is completed in section 7.3.4 Specifics of Twitter analysis.

Twitter as news media

As noted above, Twitter is a multidirectional communication channel where the general public –in Spain, 16.2% of adults had a Twitter account in 2019, according to the CIS barometer survey–, politicians, journalists, and news media exchange messages that contain ideas, images, videos, and news. The existing literature supports that Twitter is more “newsy” than other social media platforms, meaning that it resembles more an information-sharing than a social network (Cardenal et al., 2019), where news media are essential participants and drivers of attention. Nevertheless, whereas the other news media channels previously presented the voice of the news media as almost the only one (except for the commentaries on news websites and invited writers), Twitter provides a discussion or broadcasting platform for everyone. Users, be they persons, bots, institutions, or news media organizations, publish all their content in a shared, online space. In 2009, Kwak (2010) found that in the first years of Twitter, over 85% of the trending topics were related to breaking news or news related.

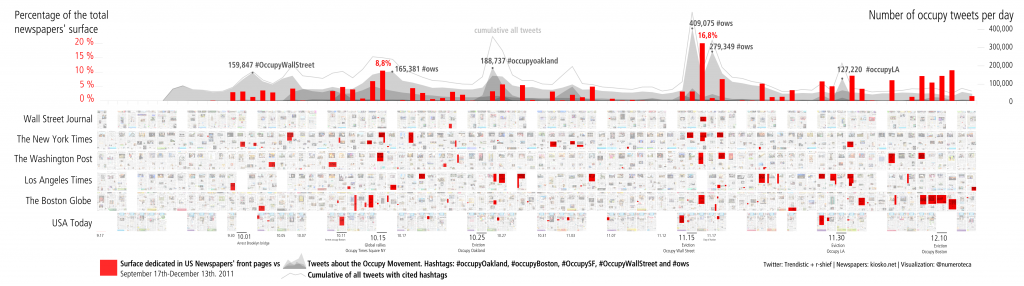

In the context of social mobilizations of the occupy movement in the USA, Nahon et al. (2013) found that Twitter activity depends on the type of planned/unplanned event or on who the event promoter is (similar to news media and blogs activity and the way they interact). Rogstad (2016) analyzed the intermedia agenda setting between top tweets and headline news in Norwegian to find that Twitter and mainstream media were consistent on the salience of many issues of the agenda, but not entirely, with the microblogging platform also paying attention to overlooked issues like the environment or gender equality. The study also suggested that Twitter contributed to the expansion of the traditional elite that influenced the agenda.

Thus, for specific issues like the social mobilizations of the indignados movement in Spain or the occupy movement already mentioned, Twitter seems more sensitive to social movement mobilizations and might create the conditions for them to be covered by mainstream news media.

2.3 Measuring public opinion #

Public opinion analysis tries to quantify the public agenda regarding the social, political, and economic situation. Since asking the entire population (of a country or the world) is impossible, personal interviews about specific and general perceptions are conducted to build the public agenda.

2.3.1 The most important problems #

There is a long tradition among scholars to use the ‘most important problem’ (MIP) question as an indicator to evaluate the public agenda in the agenda-setting literature (Funkhouser, 1973; M. McCombs & Shaw, 1972; Winter & Eyal, 1981). It has been available in the Gallup Poll since 1935, the most widely used and cited public opinion survey in the USA. For Tom Smith, the Gallup MIP series provide “a grand overview of social change, describes history from the perspective of the participants, and helps to define distinct historical periods and identify turning points” (Smith, 1985, p. 264). The possibility to follow single issue trends and cross-sectional analysis are some of the reasons that have made this data series popular.

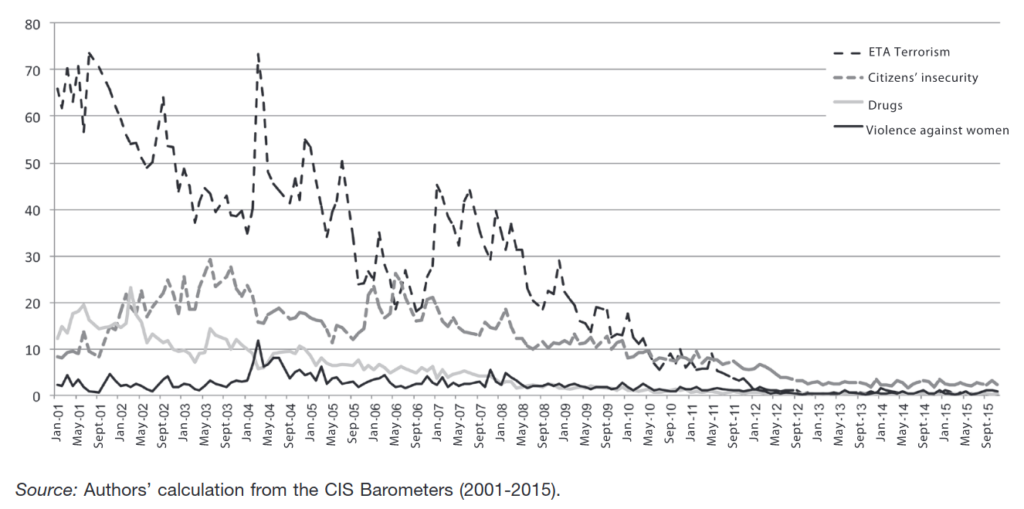

Similarly, Spain’s Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Center for Sociological Research, CIS) has been conducting monthly surveys since 2000 (except in August) where a similar question is asked: “What do you think is the main problem in Spain today? And the second? And the third?” (¿Cuál es, a su juicio, el principal problema que existe actualmente en España? ¿Y el segundo? ¿Y el tercero?) (CIS barometer, December 2011). The main difference with the Gallup polls question is that it asks for the three most important problems, not just the first one, thus providing a more nuanced, not so restrictive view of the public agenda where more issues can emerge. Surveyors annotate the open-ended answers for the first, second, and third problems and then re-code the answers in pre-established categories. This type of open-ended question has not always been the case, and, for example, in the May 1992 survey, respondents had to select three issues from a list of 10. Smith analyzed the impact of this type of design changes in the Gallup MIP series, such as –”(1) variations in question wording, (2) number of responses allowed, (3) coding categories” to name some (Smith, 1980, p. 165)– to find that they did not have a substantial effect.

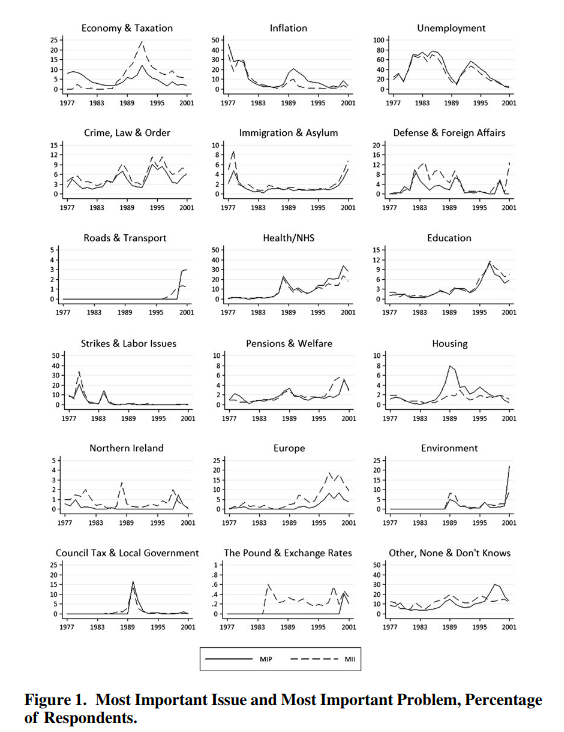

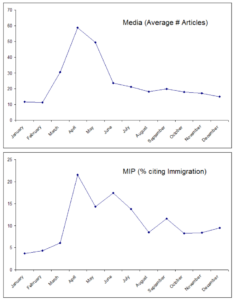

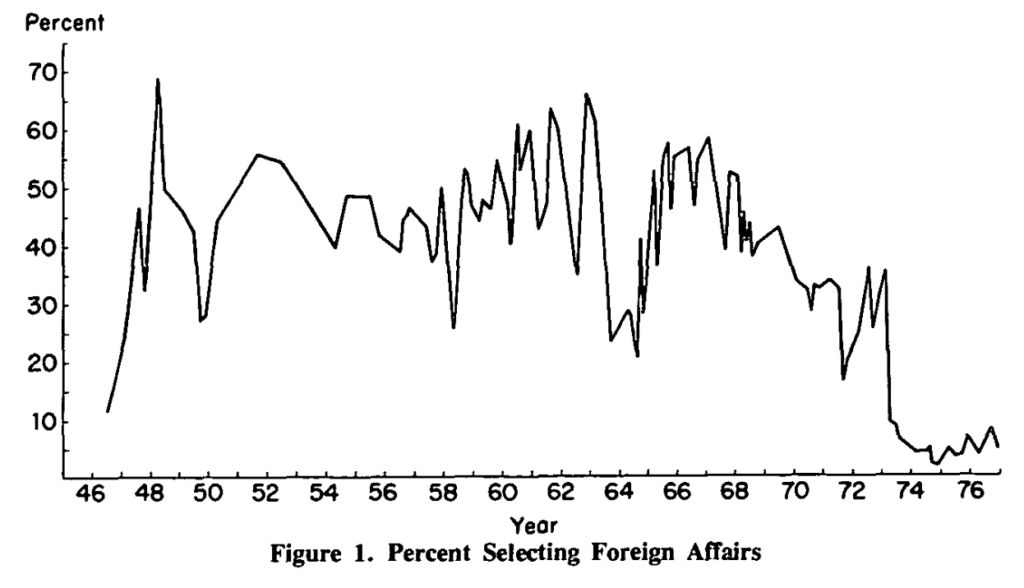

Jennings and Wlezien (2011) studied the relationship between the MIP and the MII (Most Important Issues) responses, something that is of particular interest for mass media and agenda-setting studies, where the number of news items by issue is compared usually to the MIP question to look for possible agenda-setting effects. They found that both trends are very similar, as can be seen in the following line chart:

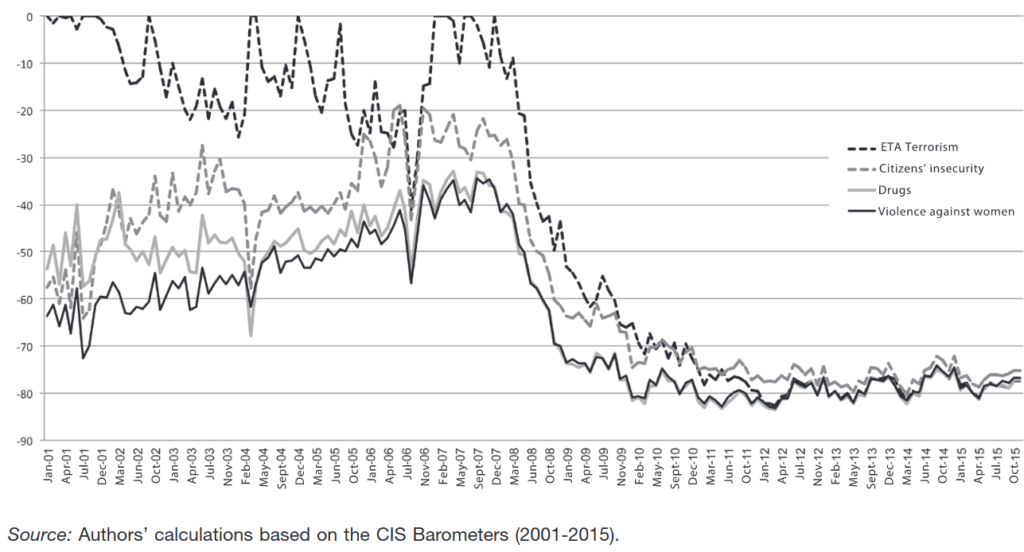

Researchers have explored different ways of using and representing the full agenda of issues resulting from the MIP responses. Caro Cabrera and Navarro Ardoy (2017), for example, while analyzing the fear of crime in CIS barometers, explained the different ways to use the MIP series: 1) aggregate intensity, the percentage of respondents who identified the same issue as a problem; 2) relative intensity, that compares the percentage of citizens who are concerned about an issue with their concern to other problems using different metrics such as (a) Aggregated view, percentage of responses that contain one of the problems; (b) Ranked issues; (c) Difference of answers to the problem with more answers in the survey. It is a measure that goes from 0 to minus 100.

2.3.2 Other metrics: Google search #

“Searches that users perform can be a good proxy for the public’s interests, concern or intentions, but these searches do not necessarily represent users’ opinions”.

(Matsa & Stocking, 2017)

The number of searches in services like Google Search, Bing, or Duckduckgo provides a proxy of people’s immediate interests. When data are available, like with Google Search, they should be used carefully as they are not representative of the entire population, and the results are not weighted like with public opinion surveys. Results for this metric would be more Internet and tech-savvy oriented, based on the type of user. Search engine results suggest a more active and immediate impulse than the one obtained from answering the MIP question in a CIS barometer survey, earlier mentioned.

Search engine streams are neither news media nor social media. They do not comply with the earlier described definitions, e.g. (boyd & Ellison, 2007). However, they are a good indicator of social responses and dynamics, provide a good proxy of people’s response to living events, and are the “entry gate” to access information to many users. Moreover, search engines have become gateways where users start browsing information on the Internet.

One of the products in their suite, Google Trends, is a free online data service that features real-time and archive search data from the Google Search engine17. Data, as far back as 2004, can be filtered by region and country and are provided on a 0-100 scale for the selected period. Data disaggregation depends on the time analyzed: hours for several days or weeks for more extended periods. According to the Google Trends page: “Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means that there was not enough data for this term”. Google Trends use a sample of the total amount of searches to provide the results18.

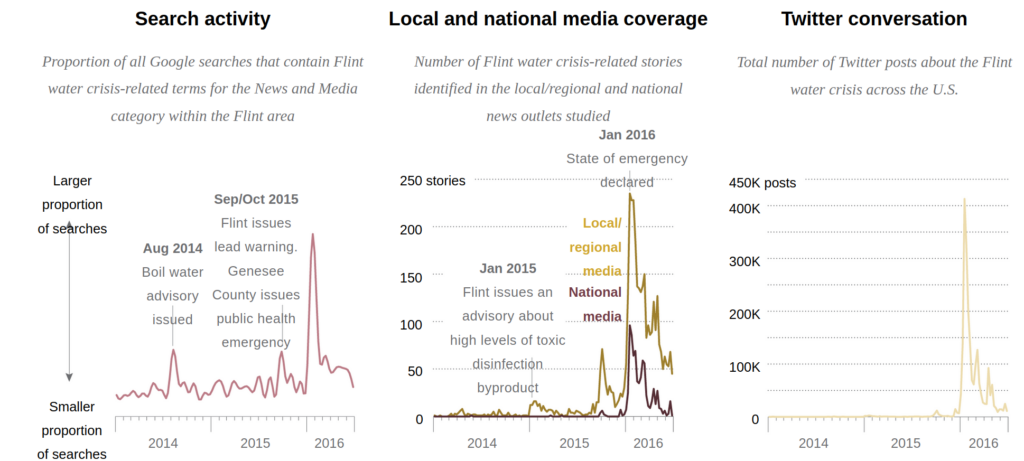

Matsa et al. (2017) showed the power of aggregated search data behavior. They showed that people in Flint in the state of Michigan in the USA “were searching for information about their water before the government recognized the contamination and before local and regional news media coverage intensified beyond a handful of stories related to the initial switch of the water supply. And, while news was the first type of information people searched for, questions about personal and public health implications soon came to the forefront.(…) Even before the water crisis had started to unfold, residents of Flint had begun searching for information about their water at increased rates – largely preceding both government notice and heightened regional news coverage.”

In their research, Matsa and co-workers used the Google Health API, which allows access to comparable data among regions (local data of Flint and for the whole Michigan state), which is not the case for the Google Trends data, that are normalized to a 0-100 scale. Normalized data can be indeed compared, but not their relative amount to the number of searches.

That is, Google search data allowed researchers to show how people’s interest came before widespread news coverage. In other key moments, they show how elevated news coverage and public search interest align with the story’s key moments. However, they also indicate that while, in most cases, search activity coincides with news media attention, the opposite, i.e., intensified news coverage, does not always translate into increased search activity. One explanation is that these new events happened in later phases of the story and consisted of incremental changes to the existing storylines, therefore not impacting search activity significantly (Fig. 36).

Granka (2010) gathered search queries of different soft (entertainment) and hard (substantive news issues) events and compared them with the volume of news coverage in print newspapers, television broadcasts, and web content (measured by counting the news items). She found that hard news search queries dropped off quickly, following the broadcast news coverage, whereas soft news declined at slower rates, paralleling the slow decline in coverage of blogs and web-only publications.

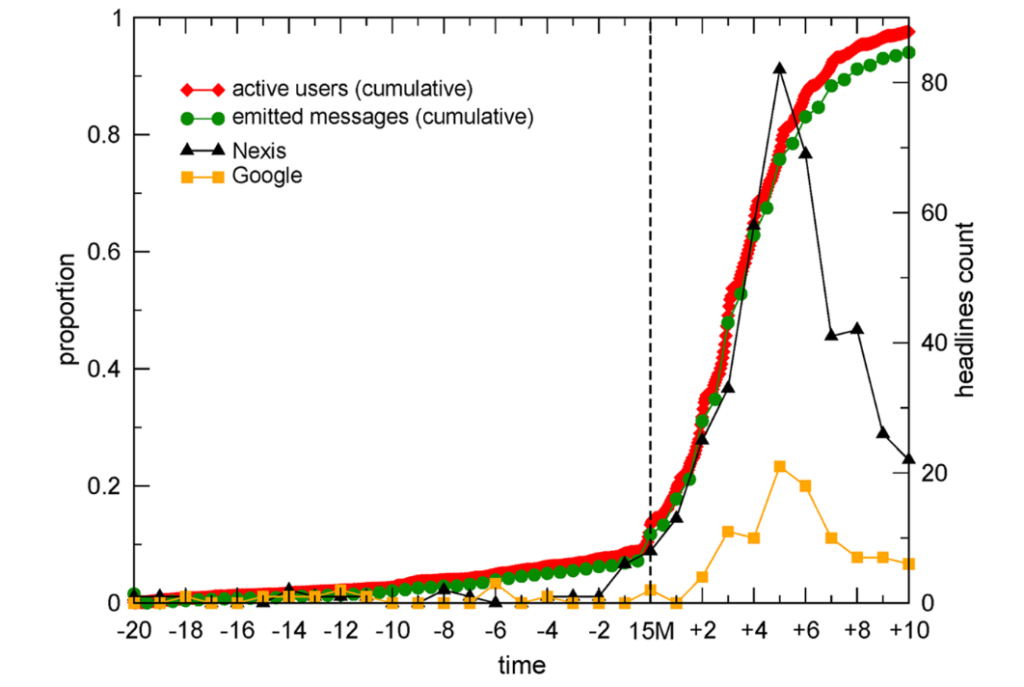

Researchers have used the accessible data of web searches to measure the importance addressed to specific stories (Ares & Hernández, 2017) or to track live events, like the evolution of diseases (Pelat et al., 2009). Mellon (2014) studied the issue salience with data from Google Trends. González-Bailón et al. (2013) compared Twitter, Lexis Nexis and Google search about the indignados movement in Spain (Fig. 37).

Theory gaps and contributions

Google Search (GS) has become popular as a proxy for public attention to certain issues, both in the academic and journalistic fields. However, there is still space for a more fine-grained analysis and to study what kind of impact GS data can record. In the present research, GS data are used in the longitudinal study (see Sec. 9.5) to show that it is more related to recent news and rapid forgetting. That is, it can be a good proxy for measuring immediate people’s interests. GS data the only non-mass media channel that serves as a proxy of mass media impact and immediate interest of the public are also used in the in-depth case study and show the same pattern of correlation as the rest of the other media channels: great synchronicity and redundancy between all the mass media channels for the average daily values (see Sec. 10.6.1). I show how, in the absence of daily public opinion data, search engine patterns are an excellent proxy to measure the concerns or, at least, the immediate interests of part of the society.

2.4 Agenda-setting #

“It may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about”. (Cohem, 1963)

Mainstream media determine what is important and what is not by selecting and framing stories and shaping public opinion. This phenomenon is called agenda-setting in communication theory. Research shows that news media have been successful in telling people what to think about, although maybe not that successful in telling audiences what to think (Cohen, 1963). Until recently, mainstream media meant principally books, newspapers, magazines, radio, and television, the latter classified as news media. Included under the definition of ‘mass media’ is the dissemination of this media via broadcasting (Luhmann, 2000).

Lazarsfeld (1944), who interviewed the same group of 600 people at different times during the 1940 USA presidential election in Erie County, Ohio, found that people acquired information from the mass media. However, not enough evidence to support important effects on opinion and attitudes. This study can be considered a precursor of agenda-setting research, which was established in 1972 (M. McCombs & Shaw, 1972) as we know and name it. It was based on the analysis of news coverage and surveys in Chapel Hill during the 1968 presidential elections. The theory has evolved much since its initial conception to prove the role of news media in the transference of salience from the mainstream media to the public agenda, providing successful explanations of events in multiple countries and situations (M. McCombs, 2004). It has studied, among other issues, the transference of salience from the news agenda to the public agenda, which is just a subtopic of the broader agenda-setting research. It has evolved since then to the second and third level agenda-setting –from attribute salience to networked agenda setting– and explored other related fields like intermedia agenda-setting, framing, cultivation theory, agenda-cutting, and agenda-melding, to cite a few.

Contrary to some interpretations, “agenda-setting theory”, which appeared at a time when mass communication theory was centered on the study of mass media attitudes and opinions in the 1940s and 1950s, did not say that the media was all-powerful but rather stressed their central role in configuring people’s minds. The theory emerged in a time when the “hypodermic needle” model19 was in place. As McLeod et al. put it, “they have diverged from an almost exclusive focus on direct persuasion and conversion effects to examining as criteria of effect other forms of overt behavior (e.g., voter turnout and political activity), knowledge gains and more subtle forms of cognitive change” (McLeod et al., 1974, p. 132).

In his 2004 review, McCombs tells the origins of the theory, starting with the classic, and much cited, book by Walter Lippmann of 1922, Public Opinion (Lippmann, 1922), whose first chapter (The World Outside and the Pictures in our Heads) which provide its conceptual basis. Drawing from McComb’s 2004 review, the phases of agenda-setting in history can be summarized in the following phases:

- Transfer of object salience (the 1970s).

- Contingent conditions that enhance or reduce agenda-setting effects (1970-1980).

- Attribute agenda-setting: moves from effects on attention to effects on comprehension.

- The introductions of other agendas (government, policy, other media, wire services). Media agenda as dependent variable: who sets the media agenda? (the early 1980s).

- Network agenda setting, when the network of issues is considered (the 2010s).

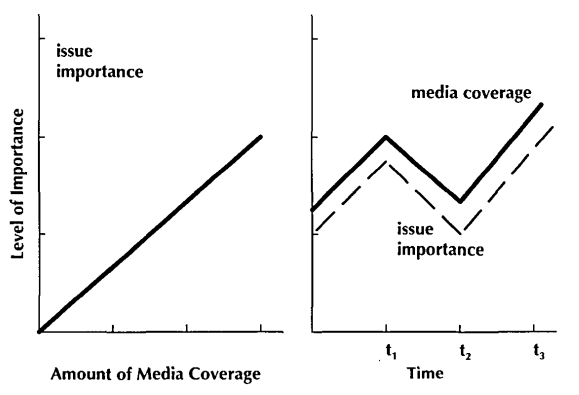

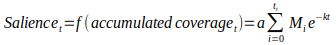

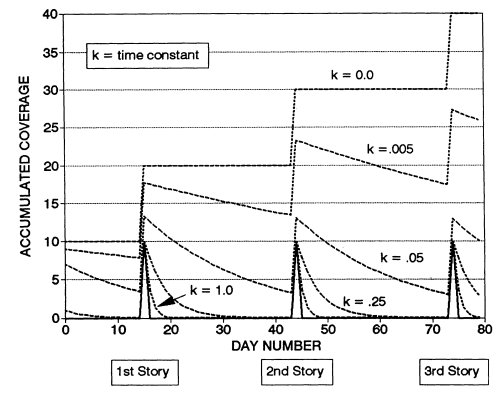

Most agenda-setting analyses assume a linear correlation between mass media attention and public opinion (Fig. 19). This type of correlation is implicit in most analyses using linear regression and calculating correlation coefficients – Pearson or Spearman’s rho– to measure the correspondence between data pairs. A few researchers have explored nonlinear relationship models (Brosius & Kepplinger, 1992; Watt et al., 1993) and warned about this implicit assumption of linear correlation in most previous studies. A linear model could fit the data many times, but others would require nonlinear approaches20.

The “Acapulco typology” (McCombs, 2004) presents four ways of conducting agenda-setting studies according to the intersection of two-dimensional pairs. The first classifies the research depending on the items analyzed to define the agenda –an entire set or narrowed to one single issue–, the second differentiates the ways of measuring the salience of items in the agenda – aggregated measures versus measures that describe individual responses.

| Measure of public salience | ||

| Focus of attention | Aggregate data | Individual data |

| Entire agenda | Perspective I Competition | Perspective II Automaton |

| Single item on agenda | Perspective III Natural history | Perspective IV Cognitive portrait |

The four perspectives in table 1 are summarized here for later reference: Perspective I analyzes the relation of the issues of the entire agenda, comparing the rank of issues in the news and public agenda as an aggregated value to establish the salience of items; Perspective II uses the individual agenda instead as a proxy for public opinion, and this model is a return to the hypodermic needle theory; Perspective III uses one issue of the agenda and compares it to the aggregated opinion values; Perspective IV focuses on an individual and on a single issue. It is used in experimental studies, where the salience of a single topic for an individual is measured before and after controlled media exposure, for example, in Kiousis et al. (1999).

Studying single issues: natural history

Agenda-setting perspective III “narrows the focus to a single issue on the agenda, but like perspective I uses aggregate measures to establish the salience of this item. Commonly, the measures of salience are the total number of news stories about the issue and the percentage of the public citing an issue as the most important problem facing the country. This perspective is named natural history because its focus is on the history of a single issue on the media and public agendas. In other words, the focus is on the degree of correspondence between the media agenda and the public agenda in the shifting salience of a single issue over time” (McCombs, 2004, p. 31-32).

Using this approach, Funkhouser (1972) and Zucker (1928), demonstrated how the agenda-setting effects depend largely on the kind of issues analyzed, if they are obtrusive, their novelty, the time it has been prominent in the media and other contingent variables mediate the strength of this effect like the need for orientation, or previous media exposure.

What follows is a series of concepts related to agenda-setting studies, together with a few examples: obtrusiveness, need for orientation, the novelty of topics, media exposure, control for reality, and framing.

Obtrusiveness

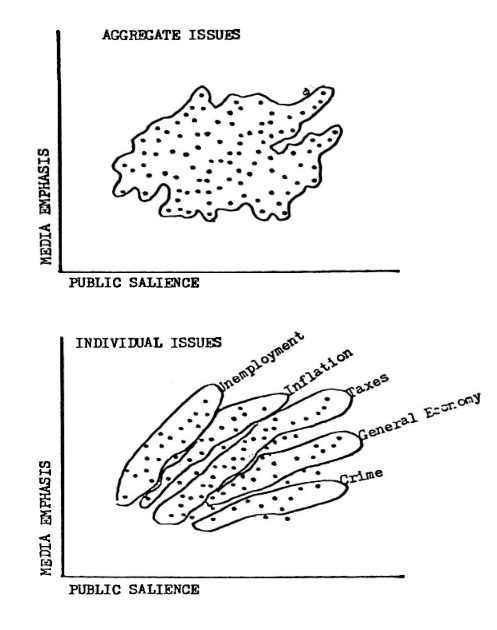

An issue is “obtrusive” if it can be known directly by the public, i.e., if the public can have first personal experience with it (e.g. conversations or direct experience). There are gray areas here, as obtrusive issues can become non-obtrusive or lay somewhere in a middle state. More obtrusive issues are (e.g. cost of living or unemployment), of which people can have direct experience in their daily lives; unobtrusive issues are known through the media. For example, political corruption (or corruption of politicians) is an unobtrusive issue, as all we know about it comes from the mass media. The aggregated calculation of correlation for various single issues of the agenda can lead to “negative correlations for the obtrusive issues were canceling out positive correlations for the unobtrusive issue” (Rogers et al., 1982, p. 2), as found it happened in Eyal (1980) doctoral dissertation. Figure 20 shows how the aggregated correlation in the scatter plot can be obscured if the single items are not considered.

Rogers et al. (1982) studied the agenda-setting effect of news media on three issues (inflation, unemployment, national unity) by counting the number of news stories in the front page of a newspaper in the previous 6 months to the survey, both cumulative coverage by month and each month separately. Their results show the great variability of the results of the correlations (Pearson) between previous coverage and public opinion depending on the months of news coverage before the survey. Two of the issues have reasons to be classified as obtrusive and unobtrusive, in contrast to “national unity” which is abstract and unobtrusive. “Unemployment” also obtained strong correlation results. These results should be observed carefully: only one newspaper was used (the Toronto Star), the analysis was carried out in only 4 six month periods (very limited N=4), and the amount of news is not relative to the total which is likely a poor measure for salience.

Need for orientation

“Need for orientation” is a psychological concept that “describes individual differences in the desire for orienting cues and background information” (M. McCombs & Valenzuela, 2021, p. 74). A person interested in a topic is likely to look for more information and be more influenced by mass media than someone who is not. The need for orientation for an individual is defined by two other concepts that occur sequentially and are related to the issues studied: relevance and uncertainty. Previous studies found that a combination of the high relevance of an issue and high uncertainty leads to stronger agenda-setting effects (Weaver, 1977). On the contrary, low “need for orientation” levels can result in a low correlation between news coverage and public opinion. Takeshita (1993) studied the agenda-setting effect of various issues. His findings showed a low correlation of +0.39 for different issues, but when he considered the 21% of the population with a high need for orientation, the correlation rose to +0.86.

Novelty

An issue’s novelty can help predict its agenda-setting effect’s strength (Watt et al., 1993). An unobtrusive issue might dissipate its influence on public opinion after a few years (Zucker, 1978). This might have relevance to the study of corruption, as we can see the decline in interest in the public agenda once the issue is not new anymore. New scandals might bring renewed attention, but old scandals might not bring new attention to a saturated media environment. “Issues that have received much coverage should show fewer agenda-setting effects than novel issues, as attention to coverage of habituated issues should be less than attention to novel issues” (Watt et al., 1993, p. 413).

Media exposure

The level of exposure to mainstream media is used as an indicator of more influenceability: more exposed to the media are more capable of being influenced. López-Escobar et al. (1996) compared levels of exposure to political information in newspapers and television news during local elections in Pamplona, Spain, in 1995, to find that the more exposure to the media agenda the greater, the transference of salience of both substantive and affective attributes.

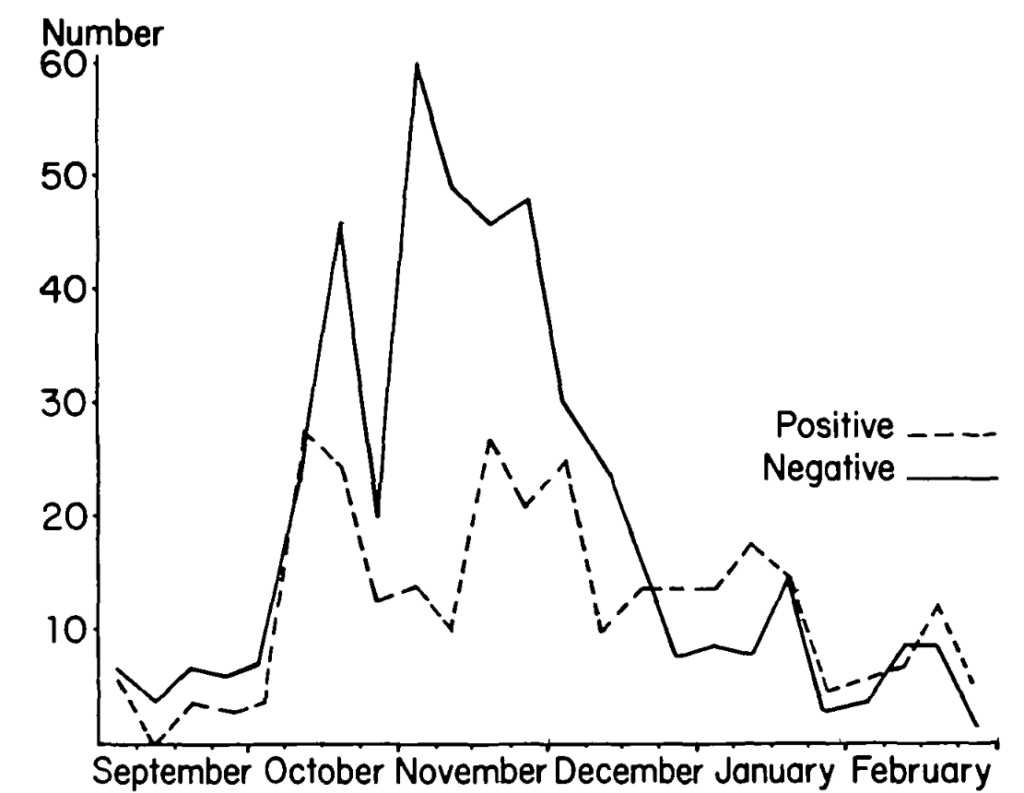

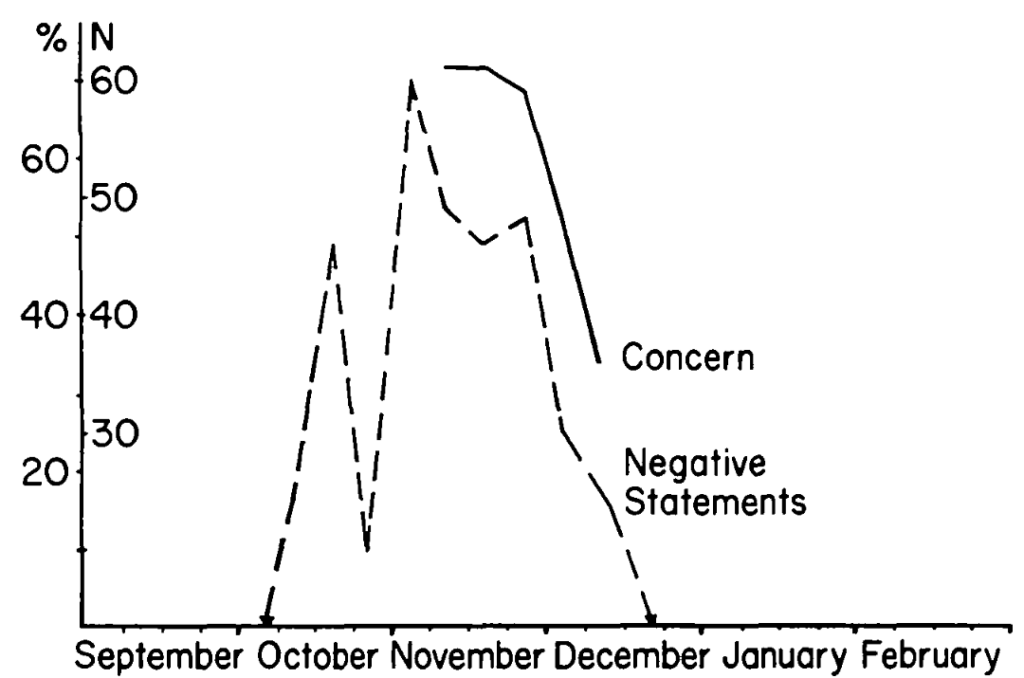

McCombs et al. (2000) analyzed news media coverage and public opinion surveys to analyze the attributes (ideology/issue positions, biographical details, perceived qualifications, integrity and personality & image classified as positive, neutral, and negative) of the three candidates Aznar, González, and Anguita during the Spanish general elections in 199621. Increased exposure to news media resulted in “both in positive appraisals of other candidates and in negative appraisals of one’s preferred candidate” (McCombs & Valenzuela, 2021, p. 48).

Control for reality

“The inclusion of ‘reality’ is particularly significant contribution to the causal evidence of an agenda-setting effect upon the public by the media because it rebuts the contention of some critics of agenda-setting theory that both news coverage and audience concerns are simply reflection of events in the real world. (…) The media are far more than a conduit for the major events of the day. The media construct and present to the public a pseudo-environment that significantly shapes how the public views the world.” (McCombs. 2004, p. 23).

The inclusion of “reality” is of particular interest for the present research, as critics of our research can argue that public opinion and news media respond to the same real-world events, but our hypothesis is that all the information that people consume about corruption scandals are mediated one way or another.

Funkhouser (1973) studied the relations of news media coverage and public opinion for single issues in the 1960s in the USA –Vietnam war, race, and pollution – using Gallup polls and TV and newspapers coverage and compared it to real-world data: “it appears that the patterns of media coverage did not have a one-to-one relationship to the realities of any of the issues. Coverage of the Vietnam war, campus unrest, and urban riots peaked a year or two earlier than these events reached their climaxes” (p. 72). The correlation between the news and public agenda was +0.78 (Spearman correlation). What Funkhouser does is to “control for reality”, to see if the public perception is a direct influence of real-world events, as the critics of the agenda-setting theory postulate, or is influenced by the media, as their strong correlation suggests. He controls the number of troops and deaths for the case of the Vietnam War, but also for other issues like campus unrest and urban riots, to demonstrate that those issues arrive at their peaks years after the peak of the media coverage and public attention’s peaks. He elaborates two ways media attention operates and follows two distinct patterns: when they cover issues based on newsworthy and non-newsworthy events. For the first ones –war, urban riots, student unrest, crime– it “seemed to involve a sort of “adaptation” of the media to the stream of events, by which a pattern of events ceased to be “news” after a while” (ibid. p 73). For the second ones they seem to be “artificial news” that can have different forms: “(1) event summaries—situations that sum up non-newsworthy events in a newsworthy way, for example, the Surgeon General’s report in 1965 on the link between smoking and lung cancer; and (2) pseudo- events—events staged to be reported in the news, for example, Earth Day, the Women’s Lib demonstrations, and various civil rights and black militancy activities” (ibid. p 73).

Similar behavior of how the media create attention, regardless of the actual situation with the oil prices, is what Kepplinger & Roth (1979) explained in their “Creating a Crisis: German Mass Media and Oil Supply in 1973-74” article, where they found that the increased coverage about the issue increased the demand of oil. They also studied the effect of negative framing and how it paralleled opinion concerns.

Gross and Aday (2003) found that exposure to local television had a strong agenda-setting effect in naming crime as an important problem in the city, while fear of crime was related to direct experience. Their study analyzed the impact of local TV news about crime in Washington, DC within the frameworks of agenda setting and cultivation theories. They controlled for TV exposure and used three measures to account for reality: direct experience as a victim of a crime, local neighborhood crime rates, and being the friend, neighbor, or relative of a crime victim. They found that “that local television news had an agenda-setting, but not a cultivation effect. People who watch a lot of local broadcast news are most likely to name crime the most important problem facing their city. Watching local television news does not, however, lead people to be more afraid of their neighborhoods or feel that they are likely to be victimized by crime” (p. 423). When analyzing for direct, or real world, experience they found that it had no agenda-setting effect but did explain fear of crime.

Framing

The second level agenda-setting studies the salience of attributes in issues or objects. If the first level is centered on the transference of salience of the main issues of the agenda, attribute agenda setting focuses on selecting and promoting certain attributes of an issue. In framing, the focus is on the “two ways of saying the same thing that produce different outcomes” (McCombs & Valenzuela, 2021, p.62), showing its origin in the framing as employed in photography and cinema: stylistic changes in perspective and camera angle and therefore relates also to page design and other graphical variables. When describing the same event, the selection of words, protagonists, and the emphasis in one part of the story or issue can give a positive or negative view and attack or a defense frame. Framing can refer to a particular frame in media content or the process of framing (McCombs, 2004).

Framing shapes our entire understanding of an issue and “call our attention to certain events and their underlying causes and consequences and direct our attention away from others. At the same time, they organize and make coherent and apparently diverse array of symbols, images and arguments, linking them through an underlying organizing idea that suggests what is at stake on the issue” (Ferree et al., 2002, p. 14). The framing of a problem or a story has a strong impact in how it is interpreted. It can impact our willingness to do something about it (or not).

In the comparative study between the USA and Germany (Ibid.), they classify ideas in news media stories about abortion and quantify the different framings (e.g. Women’s rights, Fetal life, Social justice, to name a few of the eight frames used) to analyze the use in each of the Pro, Anti or Neutral on abortion policy groups. Framing in this case comes from the social and political actors (and also journalists) that appear in the news stories.

In its most simplest form, framing can be positive or negative. If positive it would reduce the salience of an issue, like in Germany during the 1990s, where positive coverage about the integration of East Germany resulted in the decline of the integration as a problem among voters (M. McCombs, 2004; Schoenbach & Semetko, 1992). Jasperson et al. (1998) studied the public opinion from 1994 to 1996 regarding budget deficit as a problem and found that using both agenda setting and framing models together explained better opinion changes than by using each theory separately.

Framing can be applied to personal images as well as countries and issues. Some studies analyzed the agenda-setting-framing role and influence of professional public relations intervention concerning the image and portrayal of countries. Countries such as South Korea, Indonesia and others contracted professionals to have a better public image, the one that did not (Mexico) had worse performance (Manheim & Albritton, 1984).

Kim et al. (2002) analyzed the salience of six attributes related to the reasons in favor and against a new development of a commercial area in a city in Ithaca, USA, to show the high degree of correspondence between those who had more exposure to the local newspapers than to the ones with low exposure. This is a step beyond agenda setting; it is the setting of agenda attributes that occurred because mass media, newspapers in this case, defined the attributes, some in favor and some against the development plan, that modified or helped create the opinion of the public.

Maier et al. (2019) analyzed the framing of the news in a plagiarism scandal and developed the following table to assess in the content analysis process the attack and defense framing (table 2). The simple way to analyze framing (attack-defense) will be used in the longitudinal studies to have a more accurate description of the coverage about corruption (see chapter 9).

| Frame element | Attack frame | Defense frame |

|---|---|---|

| Problem definition | Violation of norms | No violation of norms |

| Public issue | Private issue | |

| Causal interpretation | Personal fault | External circumstances |

| Personality | Coincidence | |

| Full personal control | Out of personal control | |

| Moral evaluation | Condemnation from own camp | Support from own camp |

| Condemnation from opposition | Support from opposition | |

| Condemnation from other media | Support from other media | |

| Condemnation from citizens | Support from citizens | |

| Treatment recommendations | Support of: | Refusal of: |

| general/unspecific actions | General/unspecific actions | |

| resignation from office | Resignation from office | |

| personal punishment | Personal punishment | |

| defamation | Defamation | |

| A complete solving | A complete solving | |

| An apology | An apology | |

| constitution of committees | Constitution of committees | |

| structural actions | Structural actions |

Time lag

Multiple studies calculate the differences in the time it takes the salience of the news agenda to be transferred to the public agenda. Eaton (1989) reviewed the existing common theoretical explanations about how media effects take time to appear: the two-step process of communication “in which media influence opinion leaders, who in turn influence their followers” (p. 943) or the theory of diffusion, in which the adoption of the innovation follows a sigmoidal function, where time is in the horizontal axis and adoption in the vertical.

Different studies have produced inconsistent results for the optimal time lag for agenda-setting effects. To cite a few results: 2-6 months previous coverage before survey (M. E. McCombs, 1975); 4-6 weeks (Winter & Eyal, 1981); 0-2 weeks (Eaton, 1989); 1 week (Becker & McCombs, 1977). Note that these numbers are simplifications of more nuanced metrics that uses different databases and methodologies. Eaton (1989) notes that the differences between these findings in the literature, that spans from 4 months to weeks, seem more driven by the methodology of the analysis than by theory.

Other researchers have studied the different time-lag effects by media channel. Wanta and Hu (1994) analyzed time-lag effects for 5 different media types (TV, local TV, local newspapers, regional newspaper, and news magazine) in the USA and found that television had a shorter time-lag effect than newspapers.

Graphical representation

Most agenda-setting studies use tables to compare time series of news coverage and opinion surveys and correlation results. Only a few use data graphics to explore the data, usually with double or triple vertical axis timelines where news and opinion values are represented as lines connecting the data points.

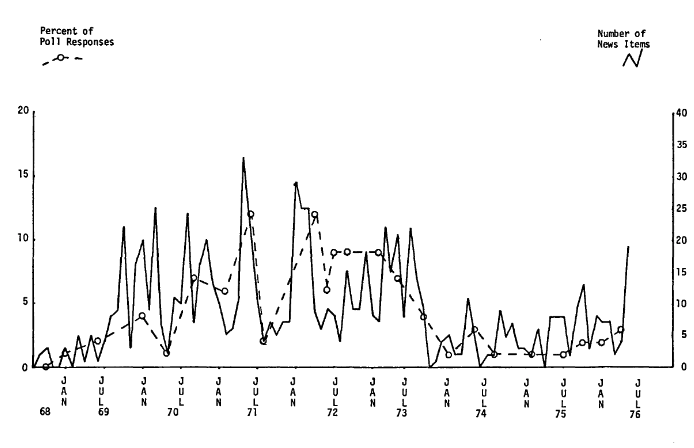

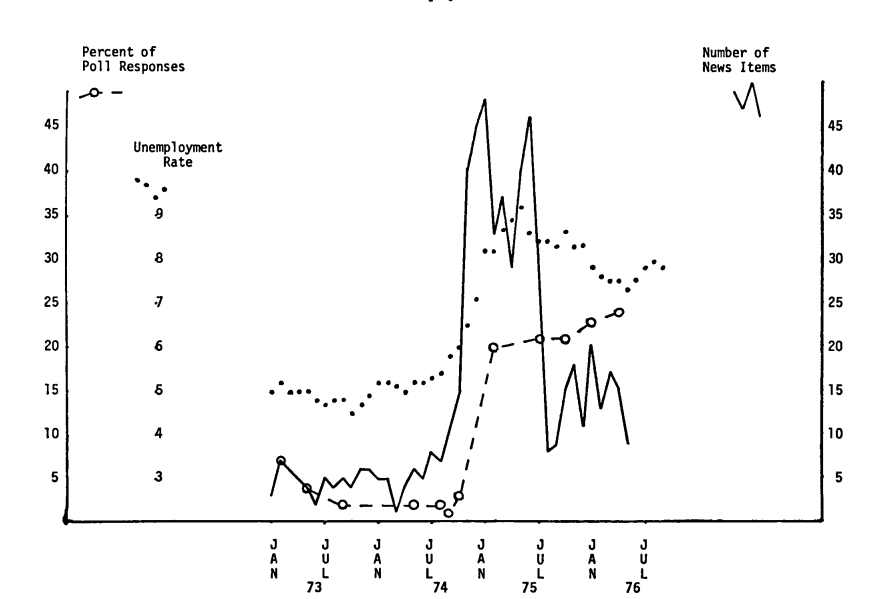

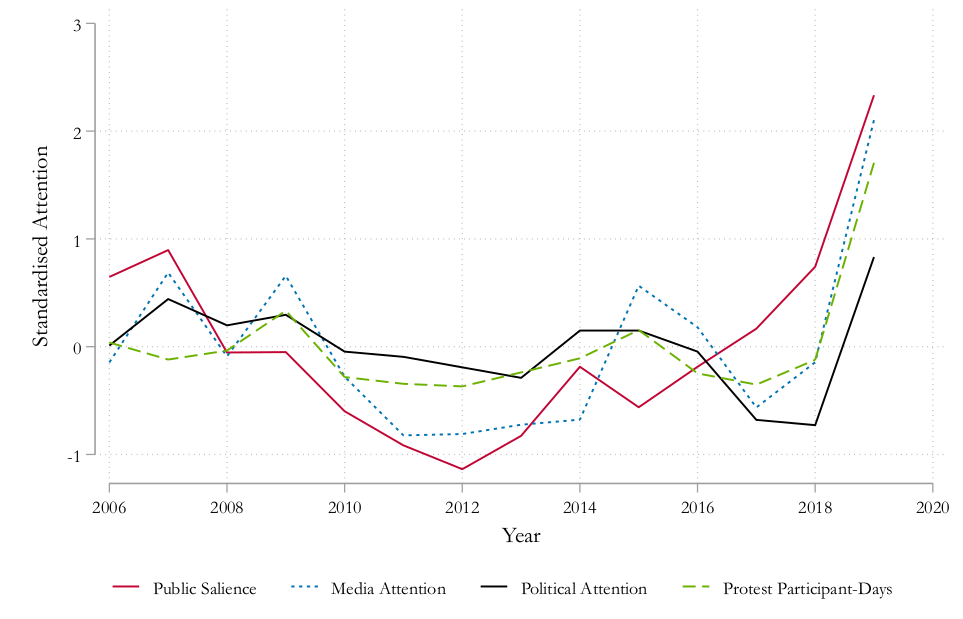

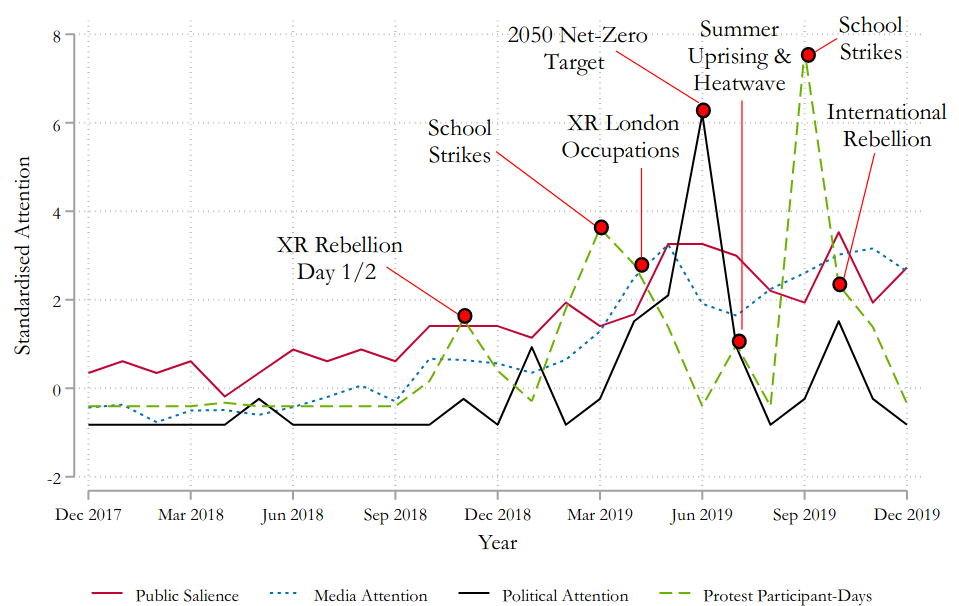

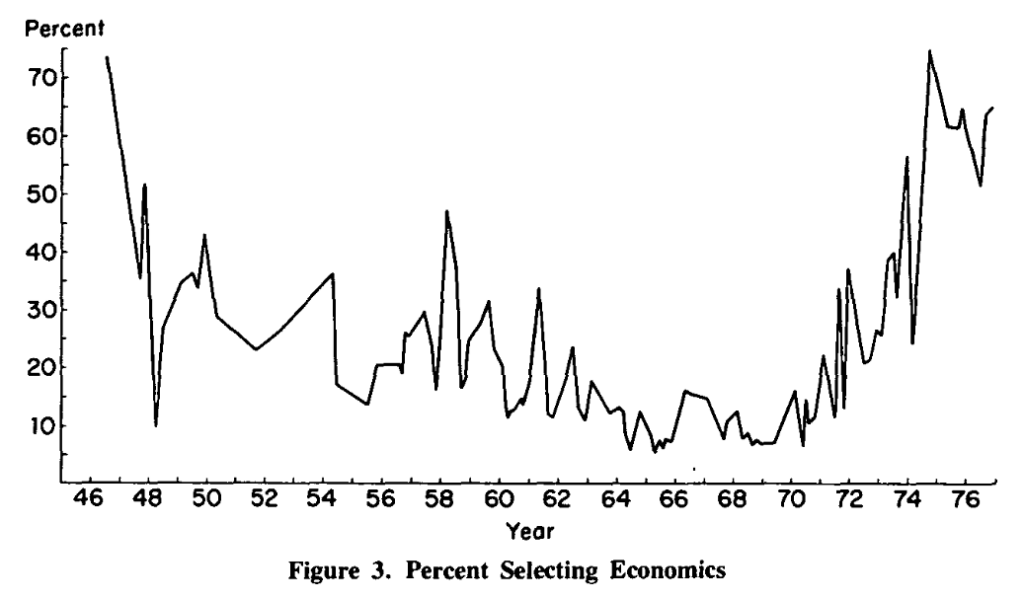

Zucker (1978) compared graphically daily averaged news media attention and public opinion using a double axis for single issues (Fig. 42). For the unemployment issue, he added a third axis with the unemployment rate (Fig. 43) to compare with “real world” data:

Double scales are suitable for comparing different scales but must be used with great care. Sometimes the axis scales are set arbitrarily and do not match, for example, the peaks of both curves. In others, the juxtaposition of curves of lines can suggest spurious relations if the analysis is centered on crossing the curves or other graphical artifacts. In Fig. 24, for example, the peak height of the three data series is very different (news > opinion > unemployment rate) and has been set arbitrarily.