Spain’s media ecosystem and corruption scandals are vital issues to understand the context before analyzing the impact of news and social media on public opinion. In general, the Spanish mass media ecosystem shares the main characteristics of other Mediterranean countries in Europe in the 21st century, where hyper-connected, mobile, multi-platform, and digital Internet-based media with intense social media presence are the norm. The strong polarization and partisanship of the media and the multi-language and differentiated news media consumption across regions can be mentioned as some of the distinguishing characteristics. The second part of this chapter analyzes the historical context of corruption scandals in Spain since the 19th century.

4.1 News Media ecosystem in Spain #

Hallin and Mancini (2004) set the basis for comparative media ecosystem research. They show how mass media can be used politically or to serve partisan objectives depending on the system’s characteristics. According to their work, Spain has a polarized pluralist media ecosystem and is in the group of other Mediterranean countries like France, Greece, Italy, and Portugal. This type of ecosystem is characterized by low levels of newspaper circulation and readership, strong state intervention, weak professionalization of journalists (i.e., low degrees of autonomy), and high political parallelism. This last feature of media systems refers to the links between political actors or parties and the media, that is, how news media outlets or conglomerates have strong connections to political parties, resulting in ideological alignment and mutual support. For example, Hallin and Mancini describe the strong ties of the socialist Party (PSOE) to the PRISA Group that controls El País newspaper, a well-known fact in the Spanish journalistic context, to illustrate this traditional partisan solid alignment of the media.

State intervention in Spanish media is exerted through the Spanish Radio and Television Broadcast Corporation (RTVE), which controls important radio and television channels and is appointed by the Parliament (Fig. 51). This intervention is also manifested through subsidies to the news media through paid government advertising and direct purchase of copies from national, regional, and municipal corporations. Public-owned channels show high levels of partisanship, as regional and national governments usually control them.

According to Salaverría et al. (2021), in 2018, they could census 3 565 digital news media in Spain, of which 363 were not active. Of the remaining active 3 202 media, 38% were digital natives. In other words, of news media companies that started online (and therefore did not make a transition from print to online format), 42% were web-based only, and 58% combined their online presence with printed versions, radio, television, or mobile apps. This substantial proportion is indicative of the way news media organizations have diversified their distribution content production in the current digital environment that favors multimedia creation. Concerning their reach, it is remarkable that 73% of the media are locally based, from municipal to autonomous community (comunidad autónoma).

This proliferation and multiplicity of new online media must, however, not be interpreted as a manifestation of a diverse and plural media ecosystem. The total amount of digital media is high. However, it would be necessary to know the number of readers or online visits they receive, something that cannot be captured with just this one figure, to understand their comparative impact. Suppose Twitter followers is used as a proxy. In that case, the analysis of Salaverría et al. shows that among the 25 online media with more followers, 23 of them come from traditional news media: newspapers (9), TV (6), magazines (4), radios (3), and agencies (1). This slightly more accurate picture of the ecosystem indicates that most leading outlets are media conglomerates that almost predate the online and social media era.

Polarization #

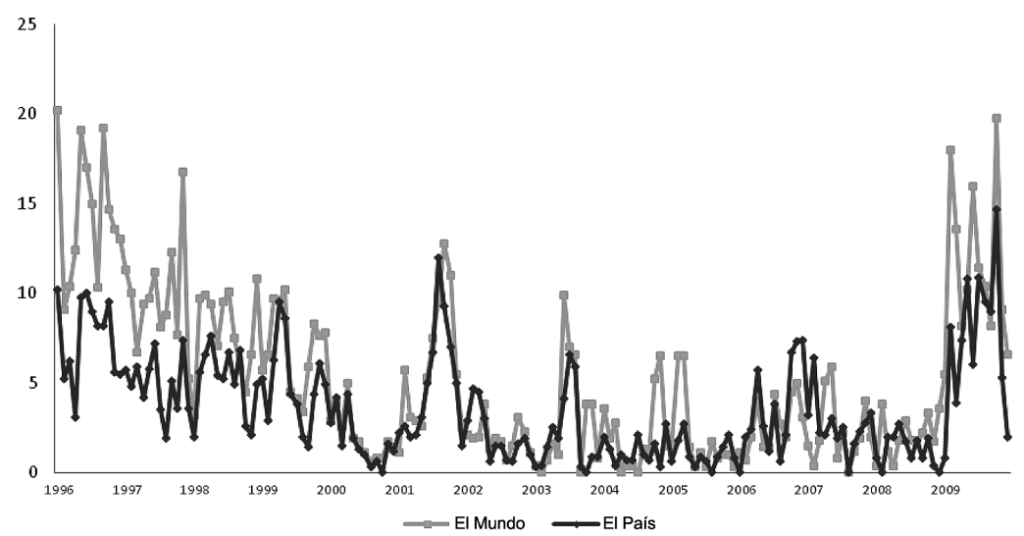

The Spanish media ecosystem’s polarization became evident in the 1990s, when an almost perfect bipartisan political system was in place. People’s Party (PP) substituted 15 years of socialist governments of PSOE, starting (for the first time since the democratic era after dictator Franco’s death) the alternation of both parties in power. Since the victory of PP in 1996, the PRISA group, formed by a conglomerate of newspapers, radio stations, and television channels (including El País, AS, Cinco Días, SER, Cuatro), adopted a critical position against the new government. Meanwhile, the group of news outlets around the telecommunications company Telefónica (El Mundo, COPE, Antena 3, Expansión, Marca¸ Veo TV) became an essential supporter of the PP (Davesa & Palau, 2013). El País and El Mundo showed strong polarization in how they covered news stories depending on the party involved (Ibid. based on Chaqués-Bonafont and Baumgartner (2013) and Baumgartner and Chaqués-Bonafont (2013)).

Blasco-Duatis et al. (2018) studied the agenda-setting of the different media groups in 2018 and structured them according to their ownership status in Spain in five types:

- Public: RTVE, the state-owned public corporation.

- Publicly traded companies: Atresmedia (including Planeta-DeAgostini), Mediaset España, Prisa and Vocento.

- Family owned: Godó group.

- COPE group, is owned mainly by the Spanish Episcopal Conference, i.e., the Spanish Catholic Church.

- Foreign investment: Unidad Editorial and Libertad Digital, belong to independent group structures.

On top of this intense concentration of media ownership, two large media groups, Mediaset España, and Atresmedia accounted for more than 80% of the income in television advertising in 2016 and more than half of the total audience, according to data by Kantar media, and together with PRISA and Mediapro control a significant part of the production of most of the audiovisual content like series, films or sports-related content (Ibid.).

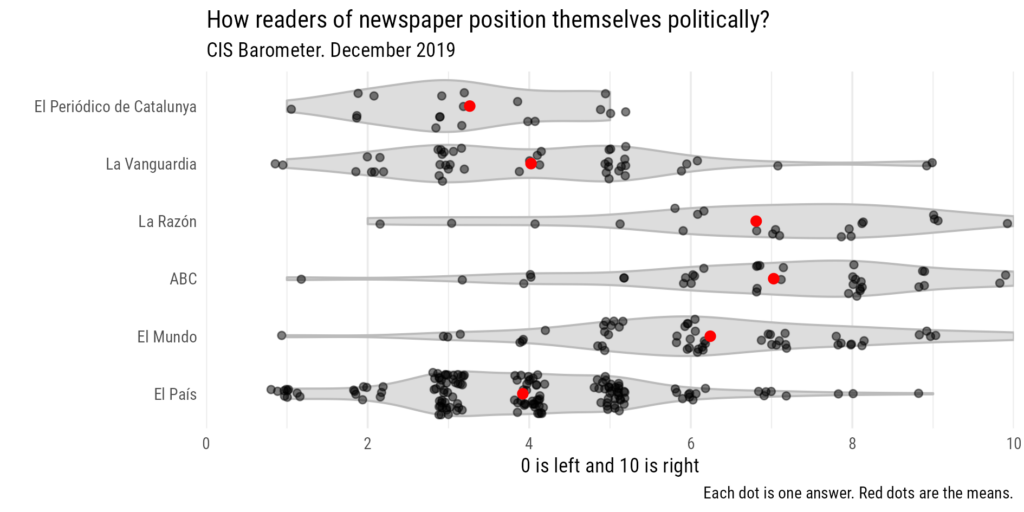

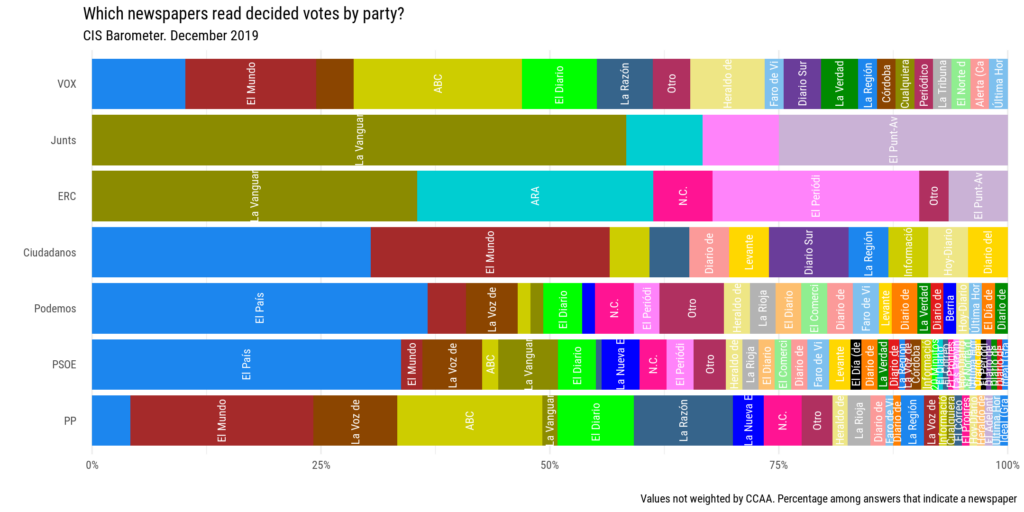

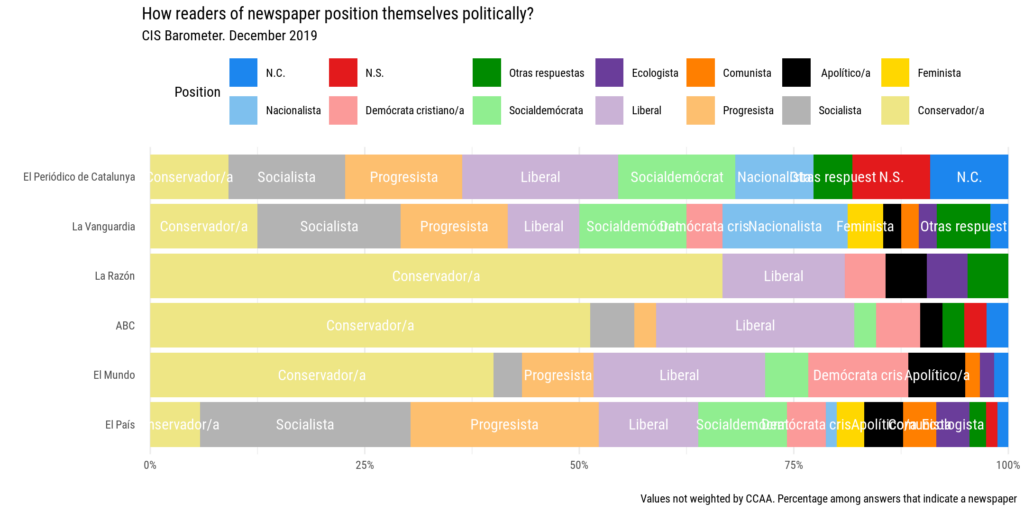

In December 2019, according to the CIS barometer (see Fig. 52), the readers of El País located themselves far to the left of the ideological spectrum (3.9 on average on a 0 to 10 scale, where 0 is the far left and 10 the far right). El Mundo readers (6.2) and ABC (7.0), the two other major newspapers, confirmed the widespread perception of them as right-leaning news media, with others (La Razón scored 6.8, La Vanguardia 4.0 and El Periódico de Cataluña 3.2). Positions have not changed significantly since 2008, when El País scored 3.59 and El Mundo 6 (Davesa & Palau, 2013). This political position is parallel to partisan election/identification, according to a 2012 CIS survey (Ibid.): the most read newspaper among POSE voters was El País and El Mundo for PP supporters. The situation had not changed much in 2019 (Fig. 53):

PSOE and Podemos show a similar color footprint, dominated by El País, followed by a multicolor readership of mainly regional newspapers. PP voters choose El Mundo, followed by ABC and La Razón, and also many other local newspapers. Catalan party voters (Junts and ERC) choose La Vanguardia, followed by El Punt-Avui and ARA, with great differences between the two Catalan nationalist parties. VOX shows a more diverse readership, close to the color footprint of PP voters, more than doubling El País presence.

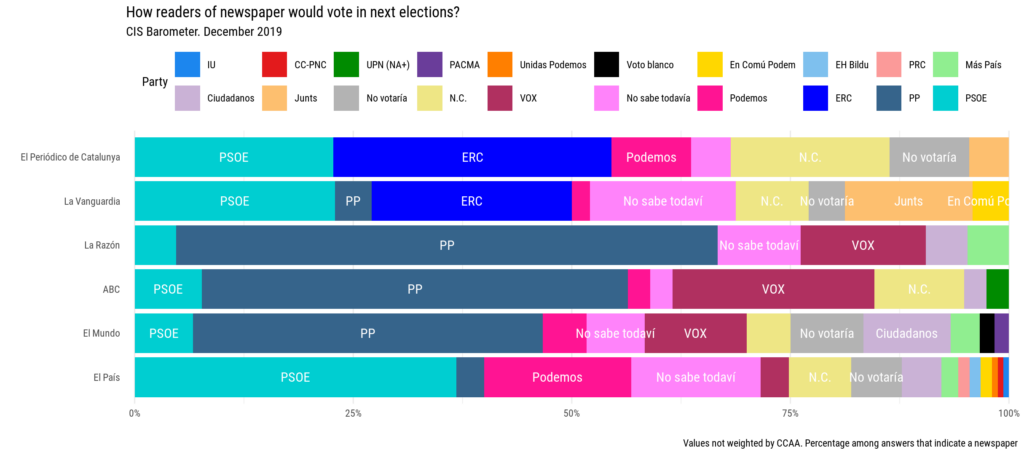

The inverse graphic1 in figure 54 (i.e., which parties are the readers of each newspaper likely to vote), shows that PP dominates the conservative newspapers (El Mundo, ABC and La Razón), followed by VOX (extreme/far-right party). The Catalan newspapers have a strong presence of nationalist parties (Junts and ERC) together with a robust socialist base (PSOE of almost 25%). For El País 37% of its readers would vote PSOE and 17% Podemos.

Ideologically there are essential differences between the readers of each newspaper El Mundo, ABC, and La Razón (Fig. 55). Such readers have a more significant share of like-minded conservative readers. In contrast, El País and the other two Catalan newspapers in the following chart have a more extensive mix of political alignments among their readership.

As Davesa & Palau (2013, p. 102) put it, “this partisan identification helps the media present news stories in a manner consistent with the ideology of their readers, since when citizens consume political information, they avoid exposing themselves to media discourses different from their own. Rather, they behave as confirmation seekers, that is, they like to read positive news about the party they voted for, and negative news or scandals the affect the party they are opposed to”. Baumgartner and Chaqués-Bonafont (2015) offer a review of the Spanish media ecosystem, the associarion between media and political parties, that is very consistent with the present analysis.

Mass media diet #

The current mass media ecosystem –digital, hyper-connected, and mobile– (Parker, 2007) has forced media groups to consider a multi-platform strategy for the distribution of their content. The shift to an “anywhere, anytime, any device” media consumption (Cagenius et al., 2006) has made offline audience metrics obsolete and forced the press and advertising industry to evolve into the integration of on and offline metrics using cross media analytics (Rodríguez Vázquez et al., 2021).

In the Spanish context, there are various audience measurement systems in place, with the Oficina de Justificación de la Difusión (OJD) for the printed press, Kantar Media for television, and Estudio General de Medios (EGM) for a multi-channel approach as the main ones (Ibid.). The CIS barometers also offer information about mass media user habits and news media consumption, although questions related to these topics are not included in all of the monthly surveys.

With the summary given in the previous pages of this chapter, some of the challenges the press and advertising industry is experiencing in determining media consumption in the current multi-channel, multi-device media ecosystem can be seen. The further goal of this section is to provide an overview of the evolution in the past two decades and to understand general trends and patterns in media consumption.

Audience measure systems #

Since 1964, OJD’s mission has been to measure the number of copies of the printed press. The data come from the news media themselves, so the gathered data need a third-party validation for the advertising industry (Ibid.). The EGM is developed by the AIMC (Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación), a non profit association constituted in 1968 by a tripartite body: news media companies, advertisers, and advertising agencies. It follows the JIC model (Joint Industry Committee) that has also been established in many European countries, mainly members of the EU, including for example Austria (print and online), Denmark (print), Finland (print and radio), Portugal (TV), Greece (Radio), Germany (all measured media) (Ognjanov & Mitic, 2019). The measurements are made by private companies contracted and audited by the AIMC. That is the case, for example, of Kantar Media, which since 2010 measures television audience, or “social-TV”, and since 2013 measures social engagement in Twitter related to television (Kantar Twitter TV Ratings) (Rodríguez Vázquez et al., 2021). The measurement systems are also moving from tracking volume (quantity) to value (quality), a way to track engagement and the time users spend on online news sites, and not only visits or clicks (Ibid.).

The EGM is the audience measurement system of reference in Spain. It conducts three surveys per year to 30,000 respondents. Researchers like Sánchez (2017) or Rodríguez Vázquez et al. (2021) warn about the distance between the actual mass media consumption habits and the EGM measurement because of the difficulty of tracking users’ news consumption across multiple devices like laptops, smartphones, tables, or connected TV. Big companies are also following this global trend toward cross-platform measurement (Brown et al., 2015). ComScore, the company that was contracted by AIMC and IAB Spain (Interactive Advertising Bureau in Spain), has moved to a total view approach, where they try to integrate multiple metrics related to television consumption across multiple platforms and devices (Santiago, 2017).

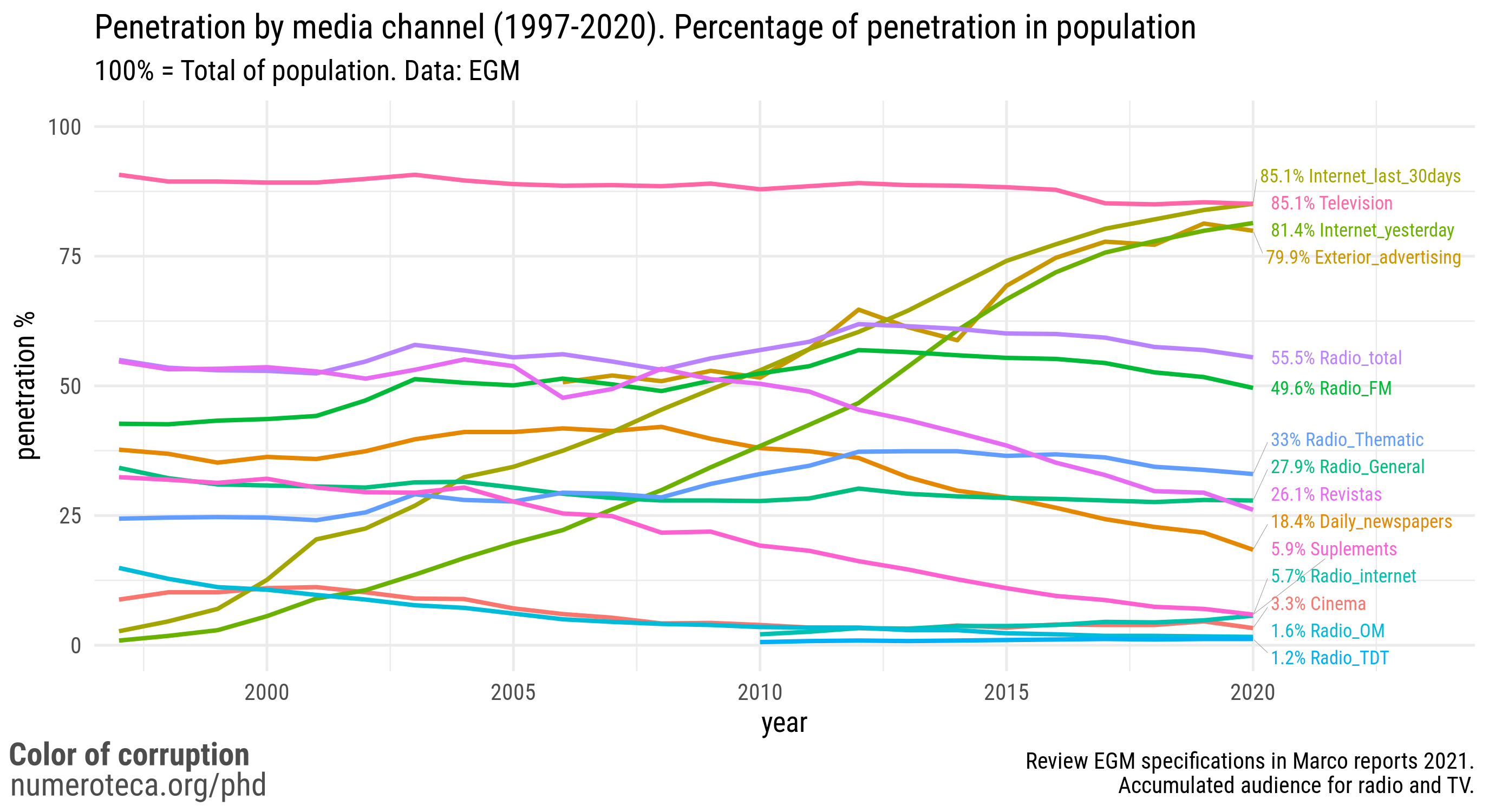

According to the EMG (AIMC, 2021), in Spain, daily printed newspapers have been losing their audience since 2008, when they reached their peak. Their penetration in 2019 was 21.7% (18.7% in 2020), while in 2008 was 42.1%. In the same period, Internet penetration, i.e., the percentage of people that have used it in the previous month, has risen from 45.4% to 85.1%, for the first time reaching a share of attention comparable to that of television (Fig. 56).

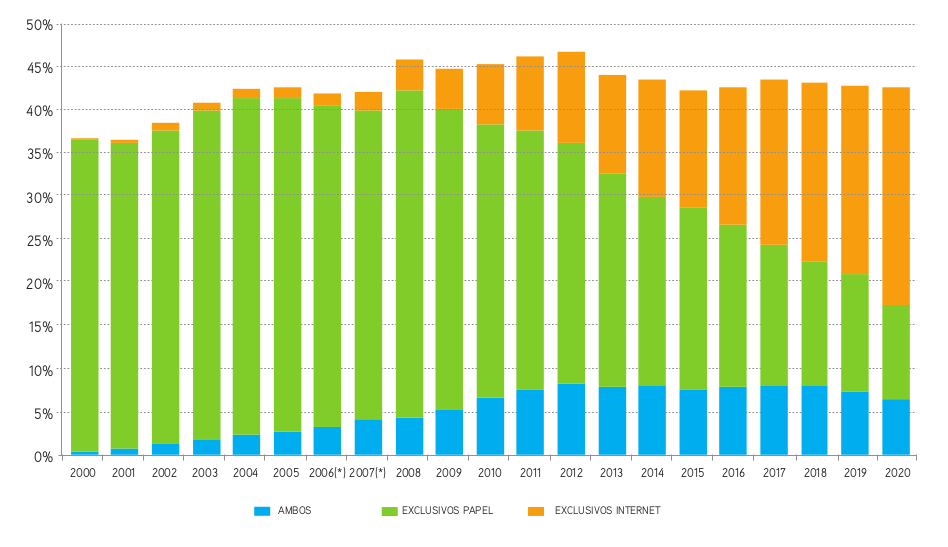

It is around 2008 when it is possible to see how the share of readers that consume news only by paper started a decline proportionally inverse to that of exclusive online news consumers. This trend seems to follow the same pattern and has not stopped (Fig. 57).

This last decade is concurrent with the birth and rise of new native online media (digital natives), like eldiario.es, elconfidencial.es, or elespanol.com, that have an important position in the digital sphere and have been able to lead the news agenda for different news stories and scandals2. Though they do not have the same prominence as printed and traditional newspapers, they are gaining a significant audience and have been responsible for discovering/showcasing several significant corruption scandals. It is worth noting that many former directors of printed media have their our news sites and are currently behind some of these digital native news media.

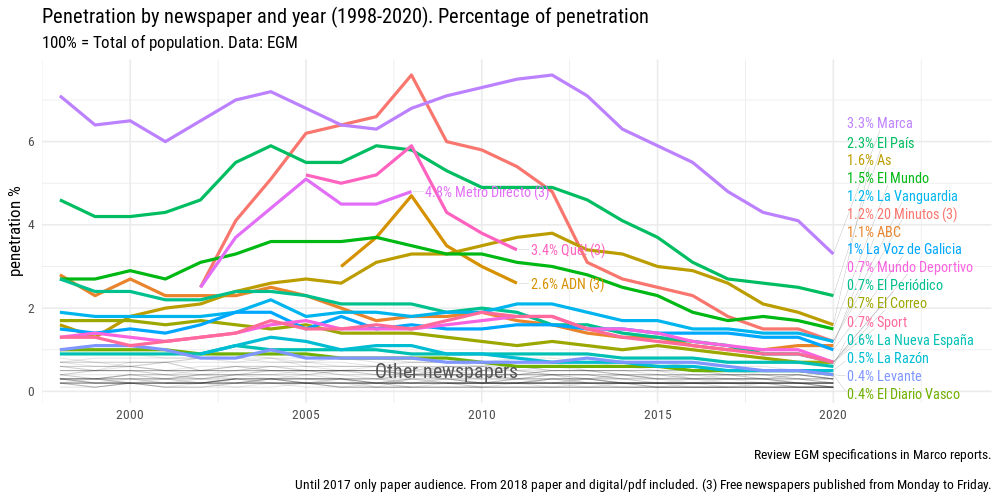

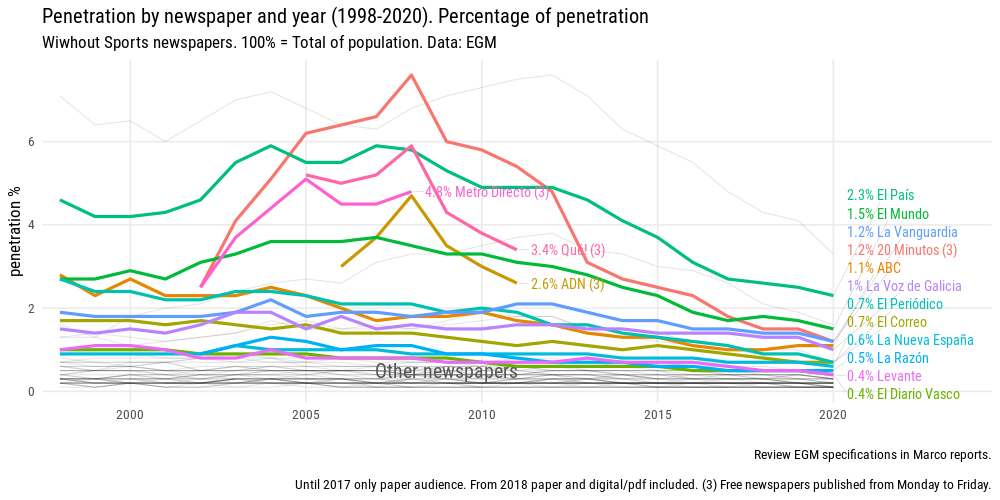

The decline in penetration of all the newspaper outlets, including those related to sports, follows the same general decreasing trend as that of the circulation of printed newspapers (Fig. 58).

If the sports newspapers are removed from the picture, the general drop in newspaper readership curve that emerges is similar (Fig. 59):

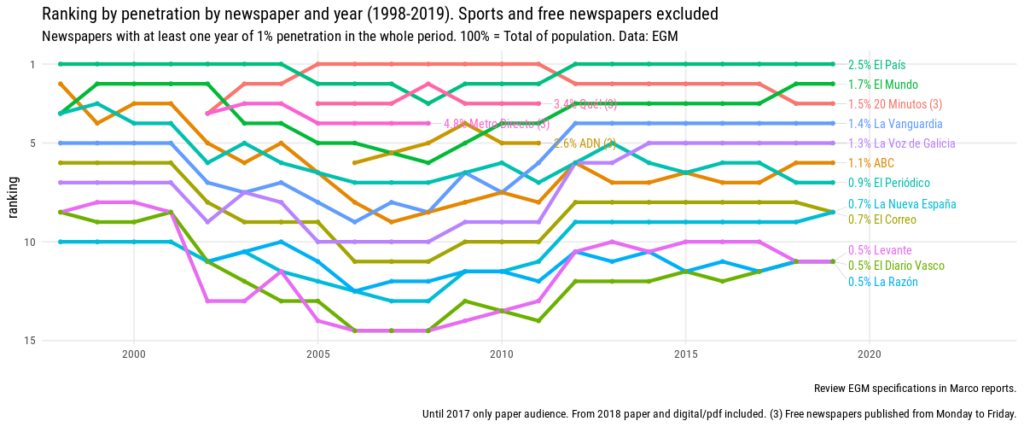

Readers peaked at the end of the 2000s decade and have continued their decline until the present. In the first decade (2000-2010) there was an emergence of new daily free newspapers (published only Monday to Friday and distributed in the principal transportation hubs and other key places in the bigger cities), that was probably powered by the economic boom during the real state bubble. Most of them disappeared (Metro Directo 2002-2008, Qué! 2005-2011, ADN 2006-2011), and only one has remained (20 Minutos, which started in2002 until the present). If the free newspapers are excluded, El País and El Mundo have been in the top 2 all through the analyzed period (Fig. 60). However, their decline is considerable: El País went from almost 6% in 2007 to 2.3% in 2020, similar to El Mundo, which went from 3.7% in 2007 to 1.5% in 2020. Their circulation loss might have been related to mobile and online news media expansion.

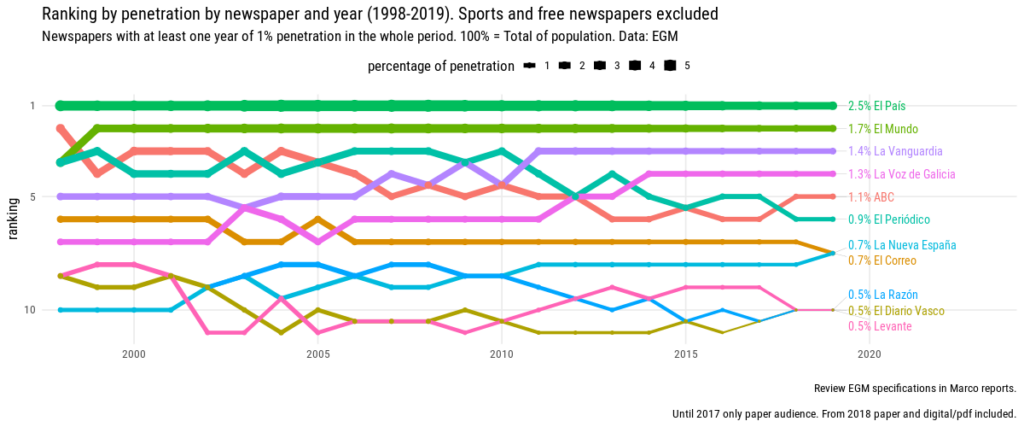

In this final chart (Fig. 61), removing sports and free newspapers, the percentage of penetration to each newspaper ranking position is displayed:

Code: pageonexR/analysis/egm.R and /pageonexR/-/blob/master/analysis/egm_penetracion.R

Media diet at CIS barometers #

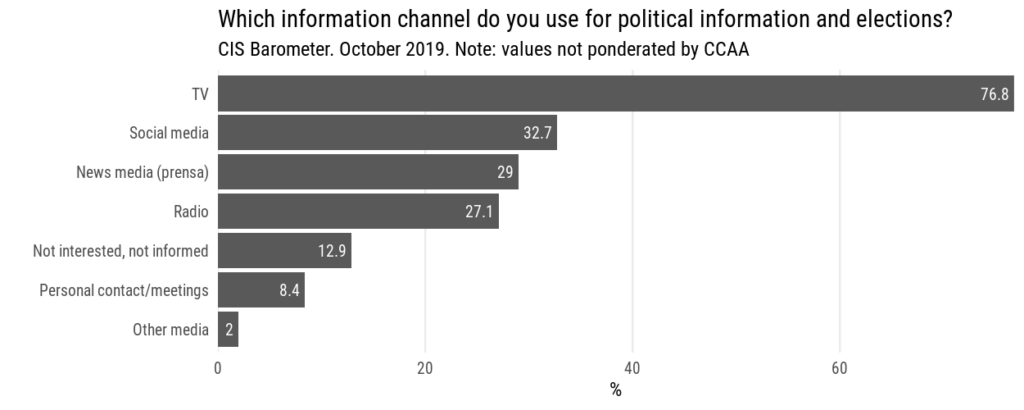

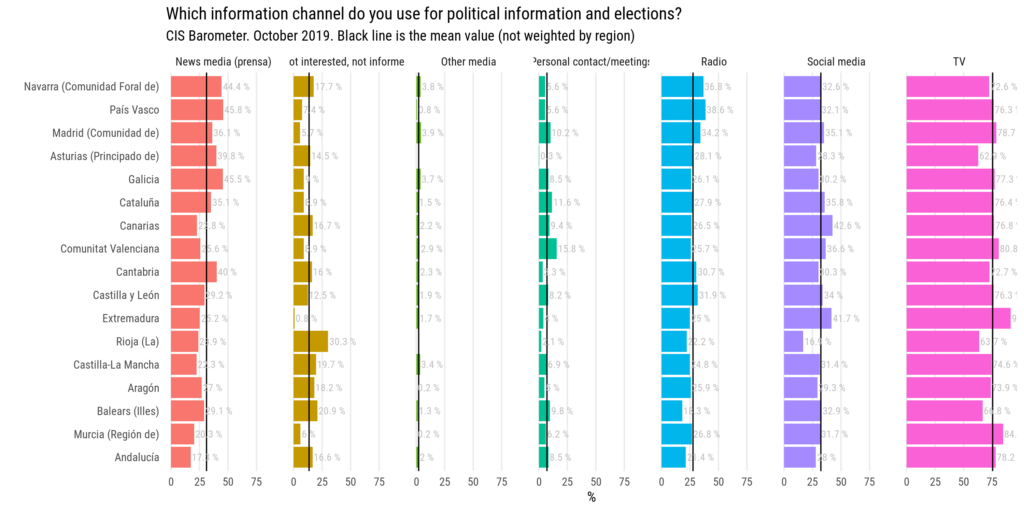

The CIS barometer sometimes asks for the news or social media diet3. For the 2019 October barometer (Macrobarómetro), they asked about the primary sources of information for the elections that took place in November of that year, as well as about politics. The answer for the first, second, and third positions have been grouped, with televisions around 60-70% for all regions, followed by radio (17-33%), social media (14-34%), and the press (12-31%) (“prensa”) that mixes both printed and digital media (Fig. 62).

The aggregated average for all the 17,650 answers of this macro-barometer gave the following results (values not weighted by CCAA): 76% television, social media 33%, new media 29%, radio 27% (Fig. 63).

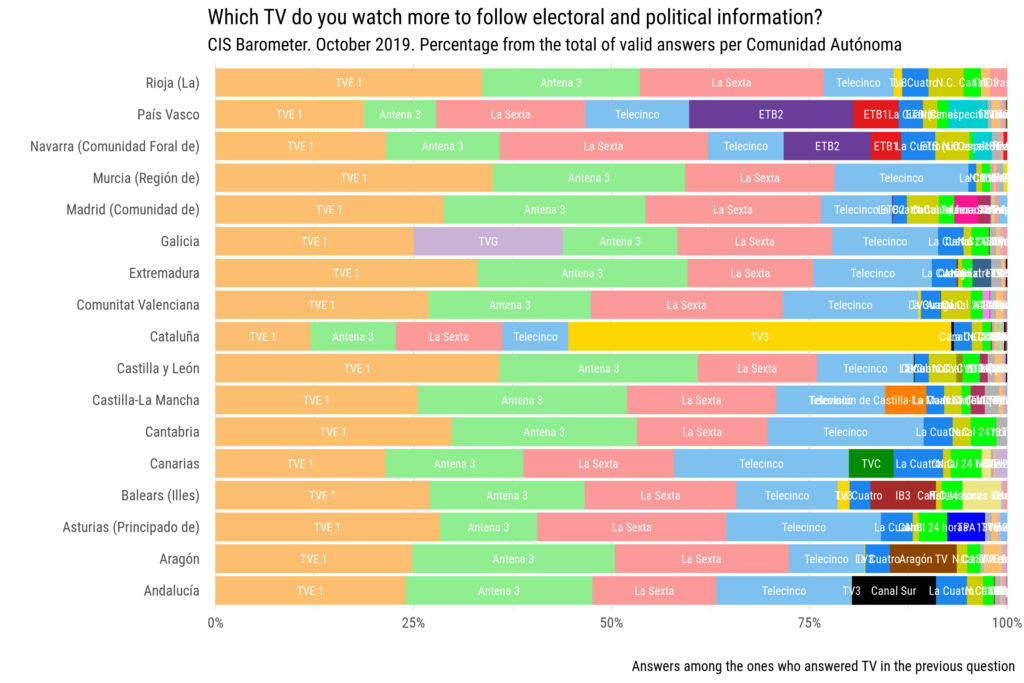

The share of attention to the different TV channels has a relatively similar color footprint for the different regions, except for the ones that have regional television channels like Catalonia, Galicia, Basque Country, and Navarra. Others have a differentiated share, but minor, like Analucía, Baleares, and Aragón (Fig. 64).

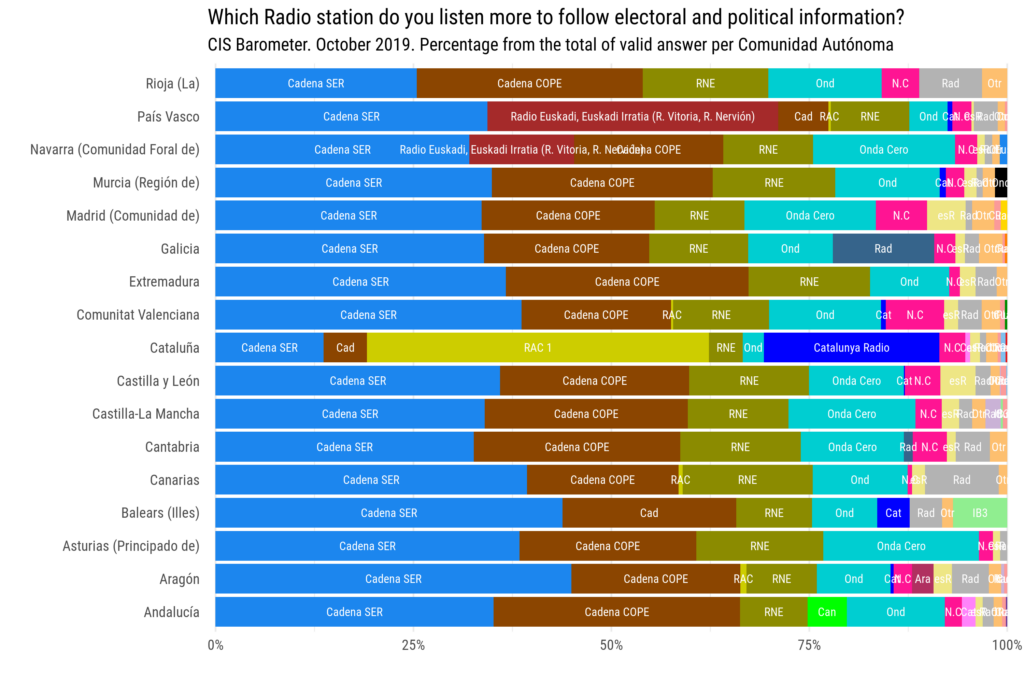

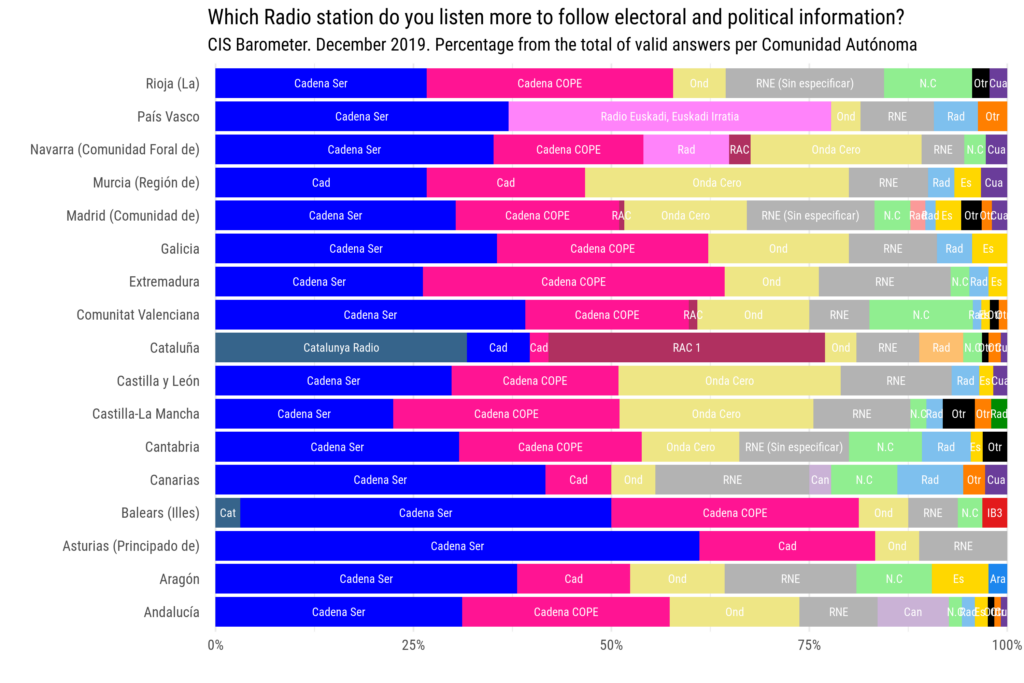

A similar pattern happens with radio consumption, where Catalonia, Basque Country, and Navarra have the most differentiated pattern, followed by Galicia and Andalucia (Fig. 65).

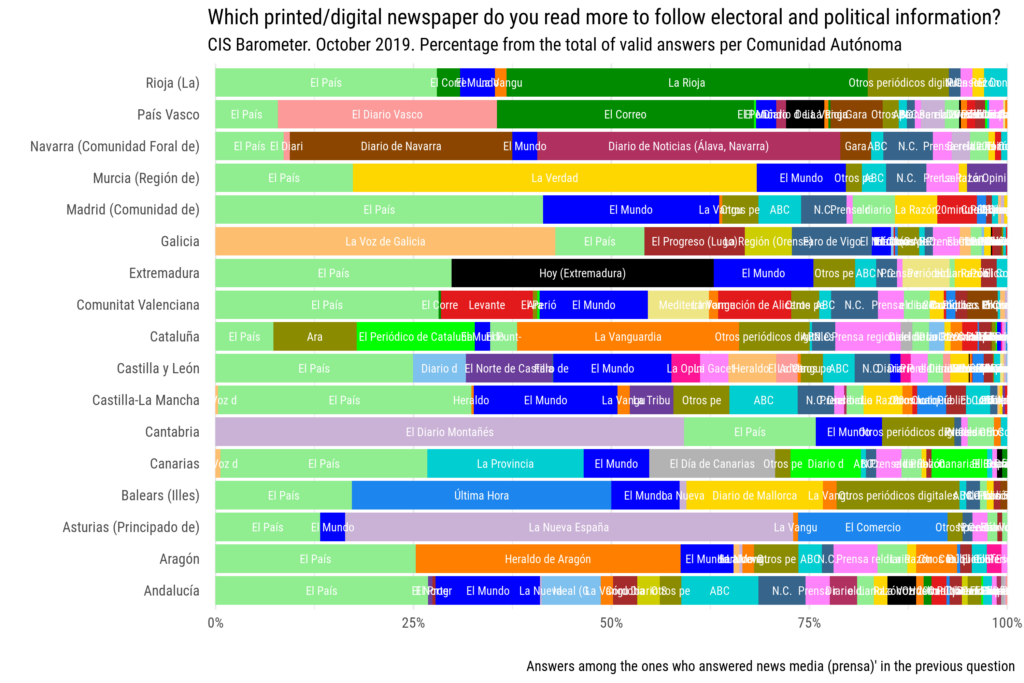

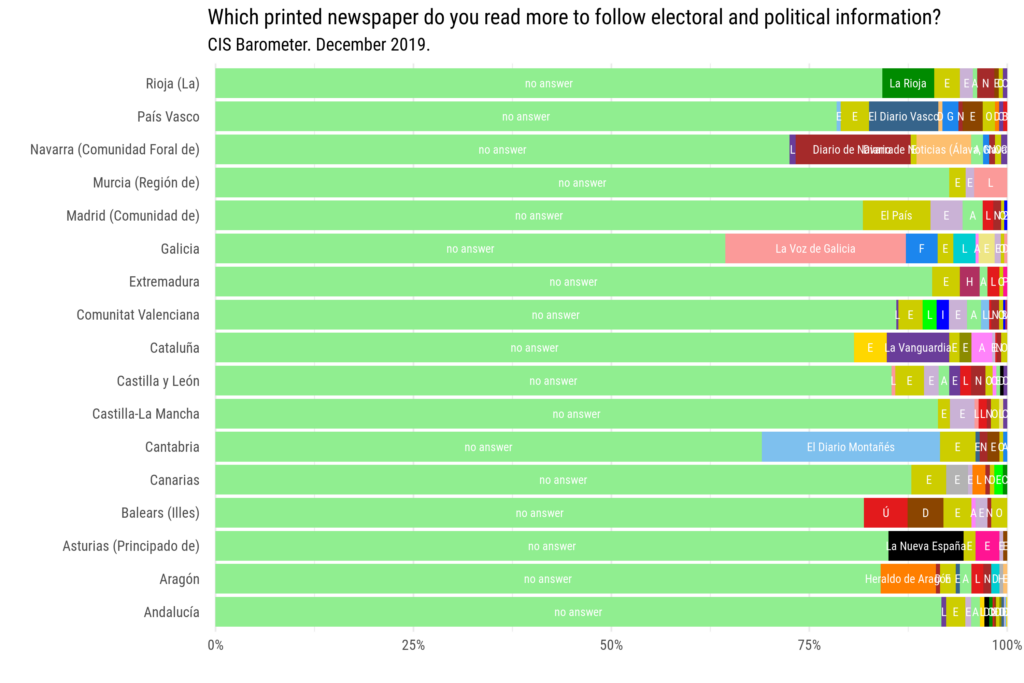

In the printed/digital sphere there is more diversity across the regions, and color patterns are very much influenced by the presence of dominant, sometimes hegemonic, news outlets, like for example El Diario Montañés in Cantabria with ~60% of the readers, La Nueva España in Asturias, LaVoz de Galicia in Galicia or La Rioja in La Rioja, Heraldo de Aragón in Aragón. In other regions, the election of newspapers is more distributed, and not only one news outlet dominates (Fig. 66).

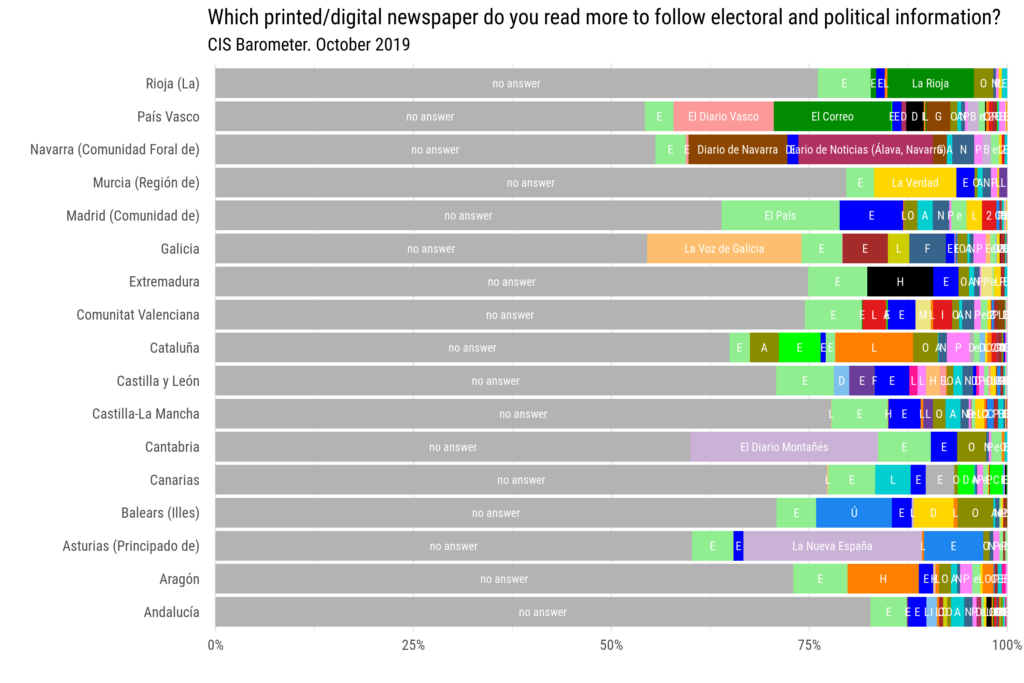

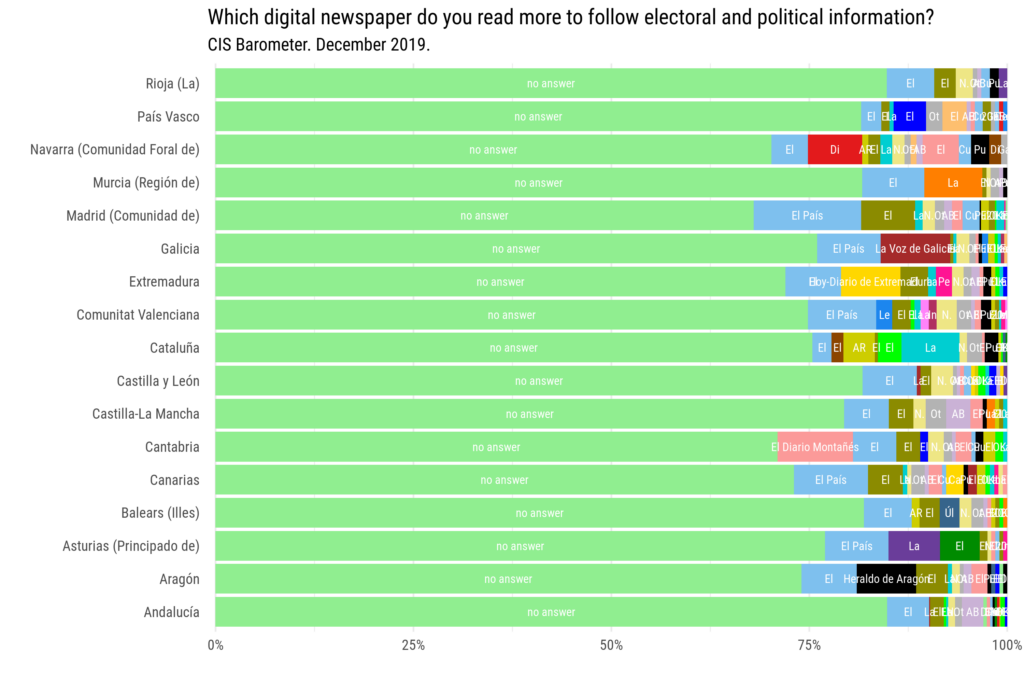

These charts often hide the reality and, for example, do not indicate the number of respondents that did not answer one or more questions. If the “no answer” are included, a different picture emerges, more accurate but maybe less informative of the impact of each media outlet (Fig. 67):

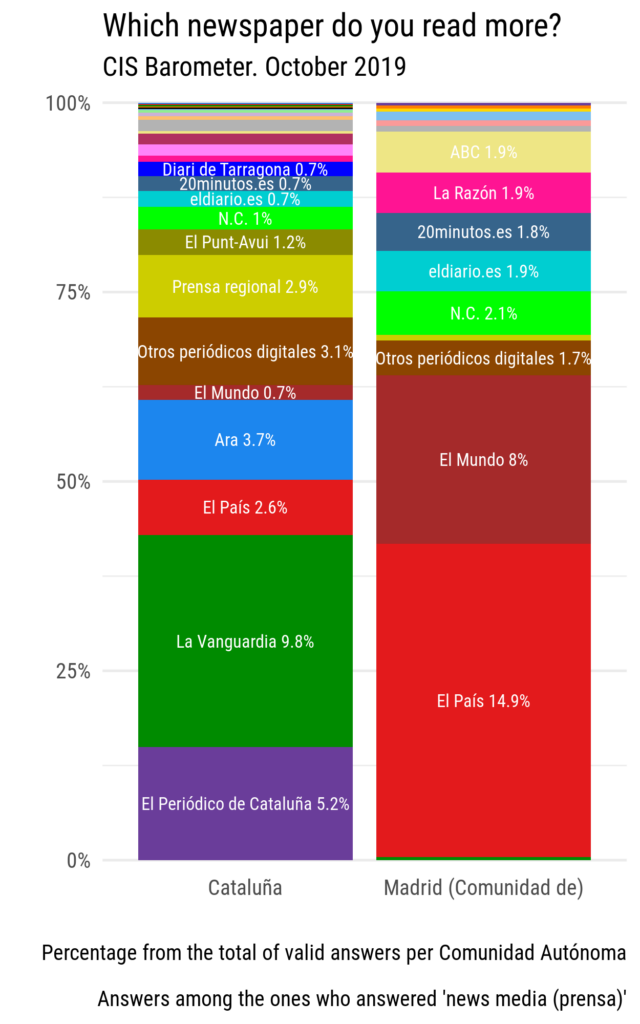

For the case of the regions of Catalonia and Madrid, a separate chart is created to see in detail the differentiated media impact of each news outlet when readers were asked what they read the most (Fig. 18). El País and El Mundo are the most read newspapers in Madrid and could be considered almost the “local” press. This analysis is used in section 7.7 Comparing regional coverage: Madrid and Catalonia.

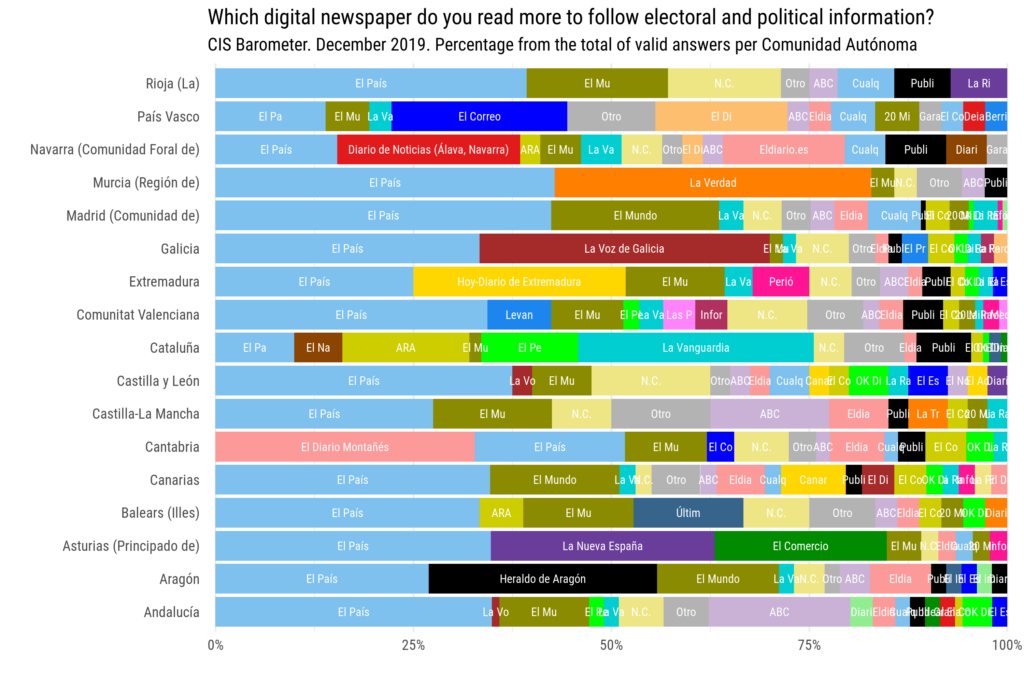

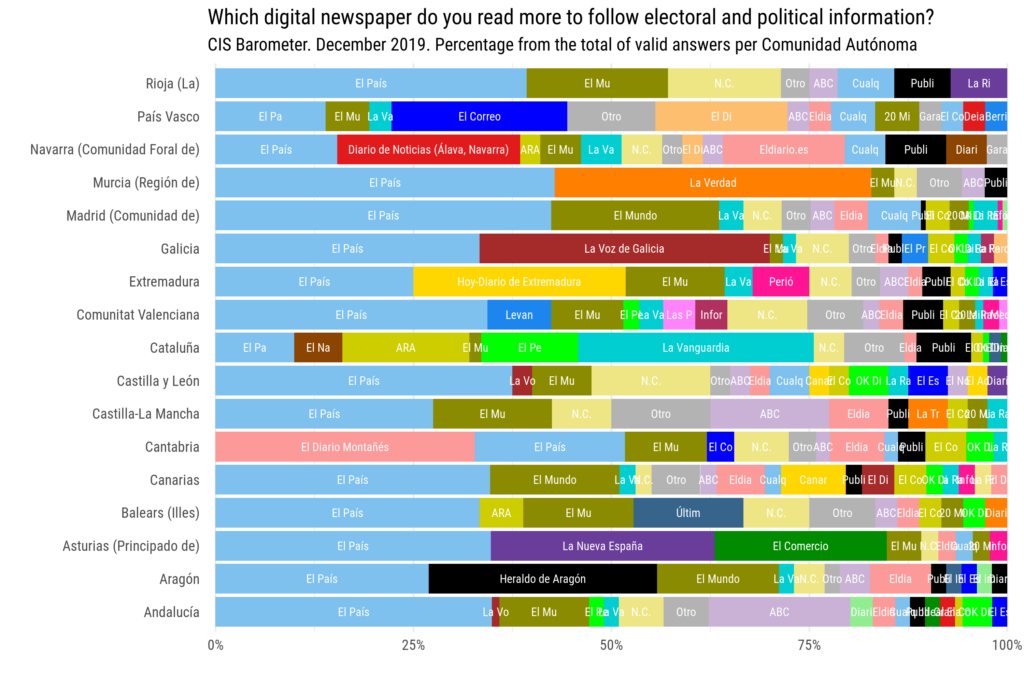

In December 2019, i.e., two months after the October 2019 Barometer, a new one post-election asked similar questions, this time centered on how respondents obtained electoral and political information and obtained similar results. According to this Barometer, there is a great diversity in newspaper consumption by region to follow electoral and political news.

The following chart shows the importance of local newspapers (Fig. 69 and 70). Though the number of interviews is low for some regions and might not be statistically significant in some cases, the different newspapers in each region are relevant and serves to understand the diversity of the primary sources of information. There is a relevant presence of El País, the newspaper considered to constitute the reference in the whole country, in almost all the regions, followed by El Mundo and ABC, sometimes also included in the same category of legacy newspapers.

Among the reported digital newspapers that are selected as the most read, El País dominates, followed by El Mundo in many regions (Fig. 71 and 72). Other local newspapers have strong presence in each of the regions: El Correo in the Basque Country, La Voz de Galicia in Galicia or El Diario Montañés in Cantabria. This is a skewed representation of the readers, as it only represents the most read newspapers. Digital natives such as publico.es or eldiario.es appear in much smaller proportions.

For the radio audience, the results are very similar to the previous survey, strong presence of local radios in Catalonia, Basque Country, and Navarra (Fig. 73):

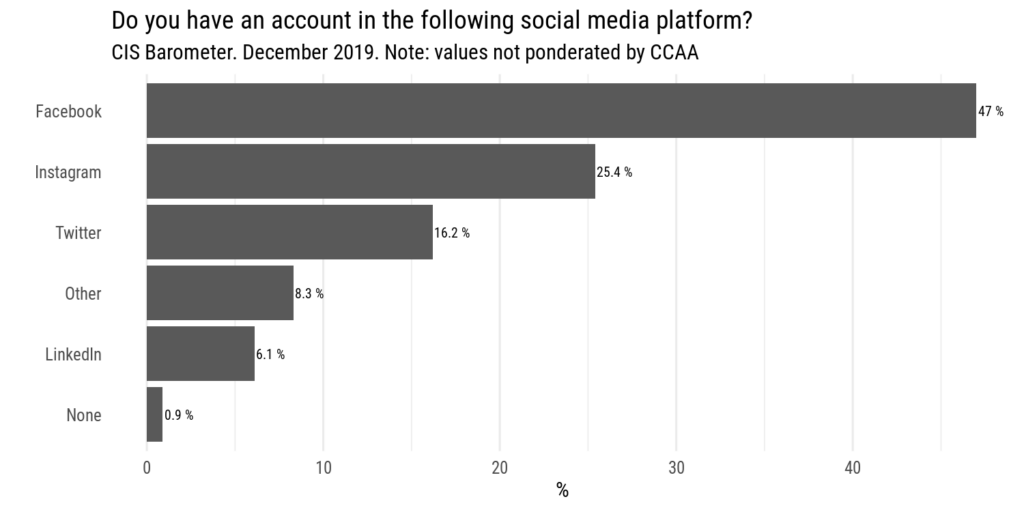

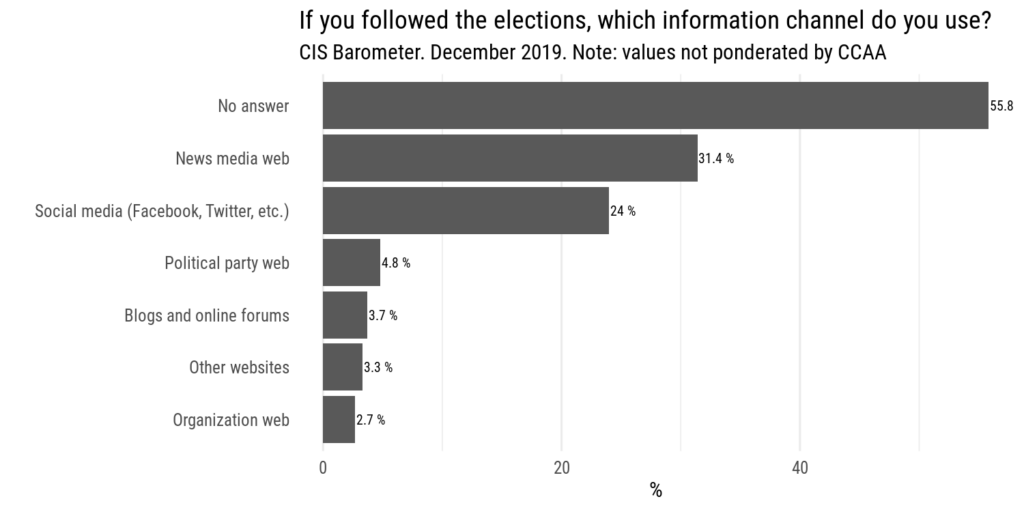

According to the same study, this is the general distribution of social media account ownership in the total population, with values not weighted by region (Fig. 74): Facebook █ 47%, Instagram ▄ 25.4%, Twitter ▂ 16.2%, and LinkedIn ▁ 6.1%. The study also showed that 31.4% of the respondents used news websites to follow the elections and 24% social media platforms (Fig. 75).

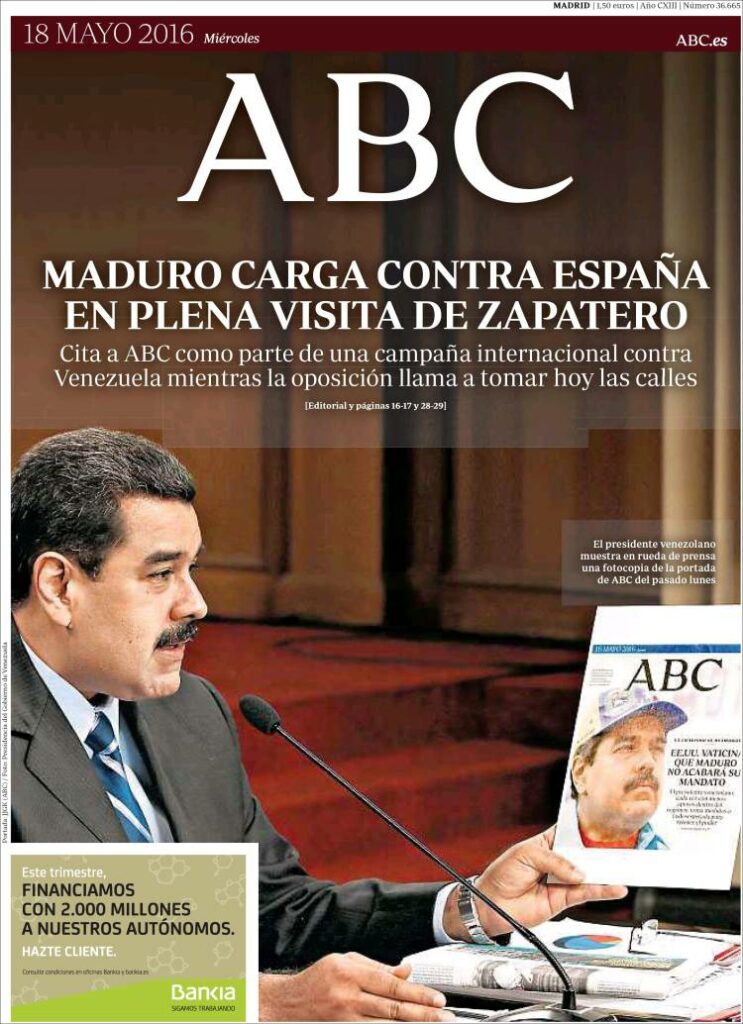

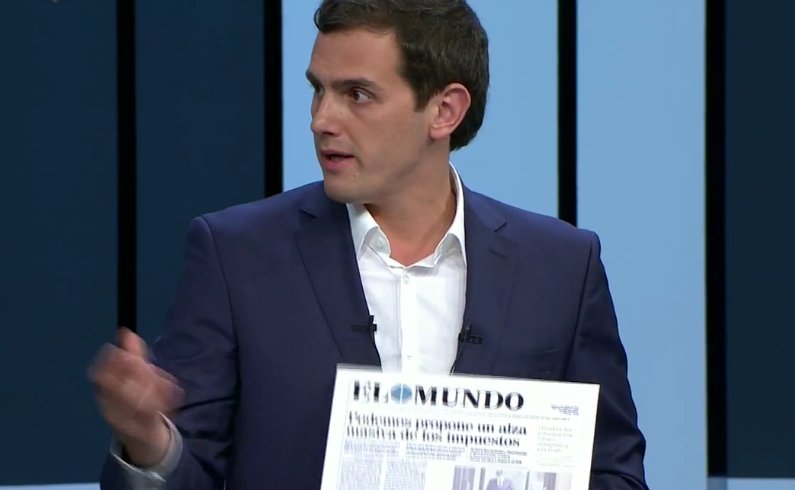

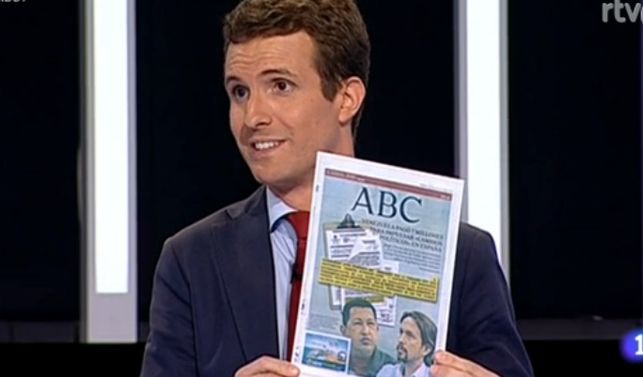

Front pages as political tools #

Before closing this section, it must be noted that front pages themselves are used as political tools by politicians in the Spanish context. As front pages condense the most important issues for a newspaper, its editorial view, they serve politicians to show proof of the importance or validation of certain issues. It helps that they are tangible objects that can be eventually printed, in contrast to the rest of the pieces of the media ecosystem.

Politicians use them to support their claims or to show that the media ecosystem is not considering important that some news outlets are misleading of preventing from publishing certain news stories:

Summary #

In summary, the Spanish news media ecosystem continues to be very partisan, has a differentiated news media consumption across regions, and an intense concentration of media ownership, formed by conglomerates of newspapers, radio stations, and television channels. Like other countries, the ecosystem has evolved into a digital, hyper-connected, mobile, social, and multi-channel environment, where Internet penetration has reached, for the first time, the share of attention comparable to that of television (85.1% in 2020) and printed newspaper penetration is declining since 2008 when the world economic crisis also hit the news media industry. In 2018, Salaverría et al. (2021) found more than 3 thousand digital news media, which indicated the proliferation of news sites, but this should not be interpreted as a manifestation of a diverse and plural media ecosystem. If Twitter followers are used as an indicator of relevance, 23 of the top 25 news media user accounts come from traditional mainstream media. Media attention is still concentrated in the same as usual media conglomerates.

4.2 Short history of corruption in Spain #

We now turn our attention to the phenomenon of corruption.This section draws from the book I co-wrote about corruption in Spain (Sánchez & Rey-Mazón, 2018).

As a first thought, it can be stated that corruption does not happen in a vacuum: The characteristics and history of a country (its population, evolution of politics, economic structure, even climate, and geography) set the basis for it to happen, or at least create the conditions that facilitate it. Uslaner and Rothstein (2016) compared education levels in 78 countries in 1870 and their levels of perception of corruption, according to Transparency International (TI), in 2010 and found a strong correlation between the two. Societies with higher levels of education in the 19th century, which usually means those where children had more years of schooling, obtained lower corruption scores than the ones that had a more unequal and deficient education. Their linear regression study also showed an even stronger correlation between the mean years of schooling and corruption levels than the country’s wealth. The levels of education in 1870 are used as a proxy that captures the level of education during the 140 years. “Sixteen of the countries with the greatest increase in mean school years were among the twenty most educated countries in 1870; seventeen of the twenty countries with the smallest growth in education were among the least educated third in 1870 (Ibid. p. 231).

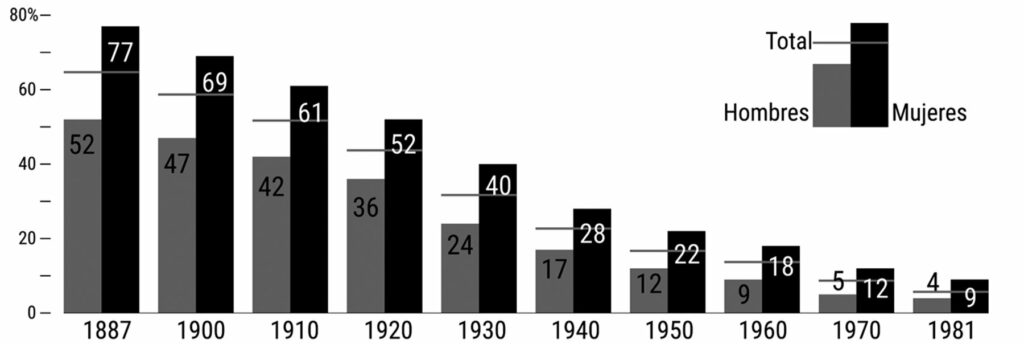

Uslaner and Rothstein point to the fact that systemic corruption is tied to a country’s existing social and historical political structure. According to the same study, the mean years of schooling in 1870 in Spain was 1.51 years on average, in contrast with 4.12 of France or 5.44 of Germany. Other related metrics to the level of education can be explored to understand the country’s situation. For example, at the beginning of the 20th century, illiteracy in Spain was around 65%, 47% in men, and almost 70% in women (Fig. 79), which also accounts for unequal access based on gender (Vilanova Ribas & Moreno Julià, 1992). In 1980, years after the establishment of democracy, 5% of men were still illiterate, as well as 12% of women. The conclusion from these figures is that a literate society is essential to processing and understanding critical news about the ruling elite. However, first, there needs to exist a counter power in the form of a free press.

Press freedom is another crucial tool to combat corruption, according to the existing literature. It creates the conditions for controlling those in power, but this can only happen if large parts of society can read and process information. That is why freedom of the press needs to be combined with a literate public to fight corruption effectively (Uslaner & Rothstein, 2016). For the case of Spain, with the exception of the six revolutionary years in 1868-1874, when the Bourbon dynasty was overthrown, it was not until 1883 that the Police and Press law was approved that allowed the publishing of books and newspapers without censorship (Sánchez Sánchez & Rey-Mazón, 2019). Following the same route, freedom of association was not allowed until 1887, many years later than other European neighboring countries (Ibid.)

Religion, and precisely the historical legacy of Protestantism, has also been cited as a critical factor in explaining the quality of institutions (Broms & Rothstein, 2020; La Porta et al., 1999). This idea is based on the notion that protestant churches wanted their parishioners to be educated, so they could read the bible by themselves, something that would not be interesting for the Catholic Church, where it was considered that this might threaten its authority (Woodberry, 2012). More recent studies have found, however, that the quality of the institutions at the macro level “cannot be explained by the doctrinal content of Protestantism, or any religion, but rather by how the institutional arrangements for financing religious practices have been formed” (Broms & Rothstein, 2020, p. 433). In their research, Broms and Rothstein match two mechanisms inherent to Protestantism: a legacy of transparency, and accountability practices at the local parish, with a clear separation of public and private money and a tradition of fiscal capacity. All these characteristics, present in many center and north European countries with a strong presence of Protestantism, are absent in the Spanish culture, dominated for centuries by the Catholic Church.

The catholic religion and moral is intrinsically bounded to Spanish society. Institutions like the Catholic Church and the Inquisition, present until 1834, are to be accounted for the structuring of the country around the catholic religion and are one of the causes of the intense political and social conservatism (Sánchez & Rey-Mazón, 2018). In Spain, political and religious power have used each other to maintain their respective status through monarchies, dictatorships, and parliamentarian periods. The clergy has used its influence to align political positions to its doctrines, and politicians have used religion for their advantage. This involvement of the Church in politics has been continuous, from the publications against liberalism in 1884 to the direct participation in the Franco dictatorship with National Catholicism (Ibid.), where its hegemonic presence controlled all aspects of public and private life. This power has continued until today, when the Church still controls a significant part of the education system (López Villaverde, 2013).

In summary, illiteracy and schooling years are proxies to measure the education levels of society and, therefore, the ability to acquire and understand information. Spain had low levels in both metrics, which, together with a late arrival of freedoms –of press and association, in the last years of the 19th century– and the strong presence and influence of the Catholic Church, nurtured the ground in the past two centuries for corruption to root. That the country lived for over half of the 20th century under various dictatorships or a low-quality democracy did not help change this situation.

To provide a comparative view, Villoria and Jiménez (2012) explain how this institutional disaffection and political detachment, which is made explicit in the case of corruption perception, is not exclusive to Spain and is similar to other south European countries. These countries have slightly higher levels of disaffection than other western countries and are inferior to ex-communist countries in eastern Europe (Ibid.). This view is consistent with Hallin and Mancini’s (2004) mass media model categorization, where Spain shares the same polarized pluralist media ecosystem system as other Mediterranean countries.

Two centuries of corruption #

The high levels of corruption and the perception of it among the Spanish citizens are not something exclusive to the last decade. It is, therefore, worth exploring the historical evolution in the past two centuries to provide context to the current situation.

As a criminal activity, it is usually hidden, so building its history remains difficult. However, traces of corruption activities and social preoccupation in the press [news media] and literature during all the different historical periods –monarchies, dictatorships, and democracies– allow for reconstructing this history. Some historians trace the emergence of corruption as a political concept to the regenerationist critique of the clientelism (caciquismo) in the Bourbon Restoration (Fernández Sebastián, 2008), while others date it earlier, to the beginning of the 19th century (Sánchez Sánchez & Rey-Mazón, 2019). As an example, in the first months of the Bienio progresista (1854-1856), the government’s cabinet asked its ministers to examine previous activities that potentially could be related to corruption, fraud, or embezzlement (Ibid.). In those years, with a rising bourgeoisie, corruption was perceived as something related to the employment created by the new Administration. Around the same time, in the 1870s, the Catholic Church, threatened by various Spanish confiscation processes during the whole century, blamed liberalism and constitutionalism for all possible evils that came from a corrupt government. Corruption has been used by conservative and liberal sides to accuse one another.

To provide an example of the recurring fraud related to property taxation and land ownership and unequal economic system, in 1900, according to Brenan (1950), concealment of land taxes was very high, and the fiscal fraud in property reached 50 to 80 percent of the total due. He mentions that Marvaud, in 1909, found that small landowners paid taxes for their land while large landowners did not. Brenan also expands this corrupt behavior to the Spanish Army, where the money for roads and equipment “disappeared into the pocket of colonels and generals” (p. 61).

In the early years of the 20th century, corrupt scandals related to the construction of infrastructures, like water dams or railways, or the organization of international events, involved members of the government and the monarchy. For example, king Alfonso XIII was accused of having intervened in the tender process of the Santander-Mediterranean railway. Examples like this make it possible to establish direct connections with recent corrupt activities where members of the national and regional governments, or the same Royal (Bourbon) family, are involved in similar scandals. We can cite as an example the commission that the former king of Spain obtained for the high-speed rail in Saudi Arabia or the Formula 1 scandal in Valencia, to name just two.

With the arrival of the Second Republic in 1931, the Parliament opened a commission of inquiry to determine the responsibilities of the previous years –Primo de Rivera dictatorship and the Alfonso XIII monarchy–. However, the proceedings did not arrive at the Supreme Court until 1934, and the Civil War arrived soon enough to impede the completion of the process. During those years, the conservative news media and parties accused the new democratic system of corruption and nepotism.

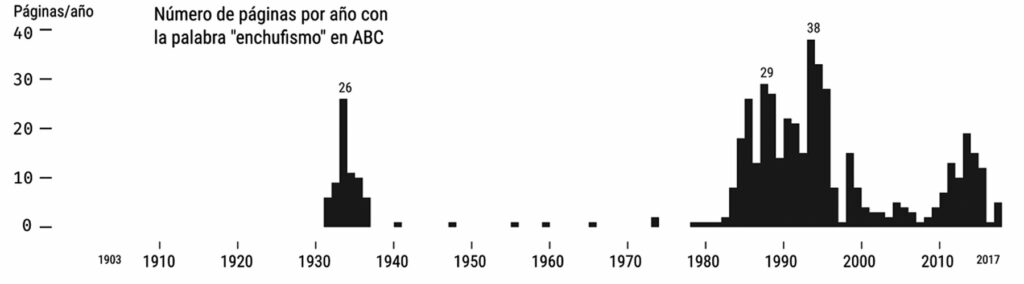

In the following chart, the amount of pages that contain the word “enchufismo” (nepotism) in the conservative and monarchic newspaper ABC shows how it closely matches the periods of democracy during the Second Republic (1931-36) and after the arrival of the socialist party in 1982. “Nepotism” was used to discredit liberal and left governments.

During the Second Republic, two corruption scandals, Straperlo and Nombela, made two governments fall and the practical dissolution of the Radical Republican Party. This influence in politics also brings resemblance with the end of two Spanish governments in recent history, surrounded by corruption and political scandals: Felipe González in 1996 and Mariano Rajoy in 2018.

The Civil War (1936-1939) brought crossed accusations of corruption from both sides. The Republic meant political, economic, and moral corruption for the rebels’ propaganda that instigated the coup. The republicans centered their propaganda on the denouncement of the corruption of the fascist army of General Franco, related to the Rif War in Morocco.

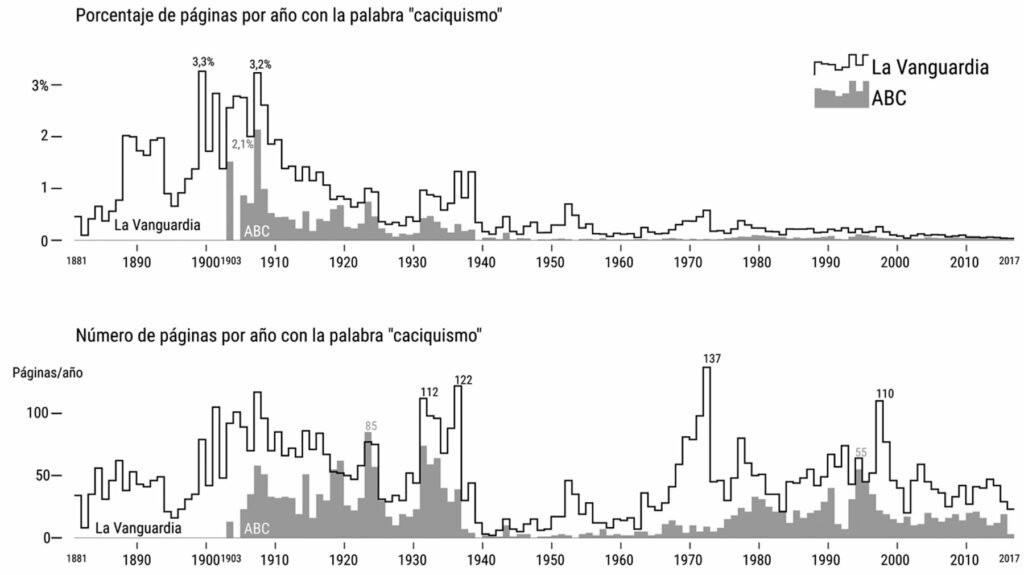

During the Franco dictatorship, according to Paul Preston, one of his foremost biographers, corruption was tolerated and used as a tool to control the elites and subordinates (Massot, 1994). There were various corruption cases that did not reach the level of scandals: Barcelona Traction (1948), Agenda Rivara (1958), Manufacturas Metálicas Madrileñas (1959), MATESA (1989), SOFICO (1974) (Sánchez Sánchez & Rey-Mazón, 2019). Figure 81 displays the pages that contain the word “caciquismo” in ABC and La Vanguardia newspapers (see section 6.3. It shows how the word almost disappeared from the newspapers in 1939, just after the Civil War.

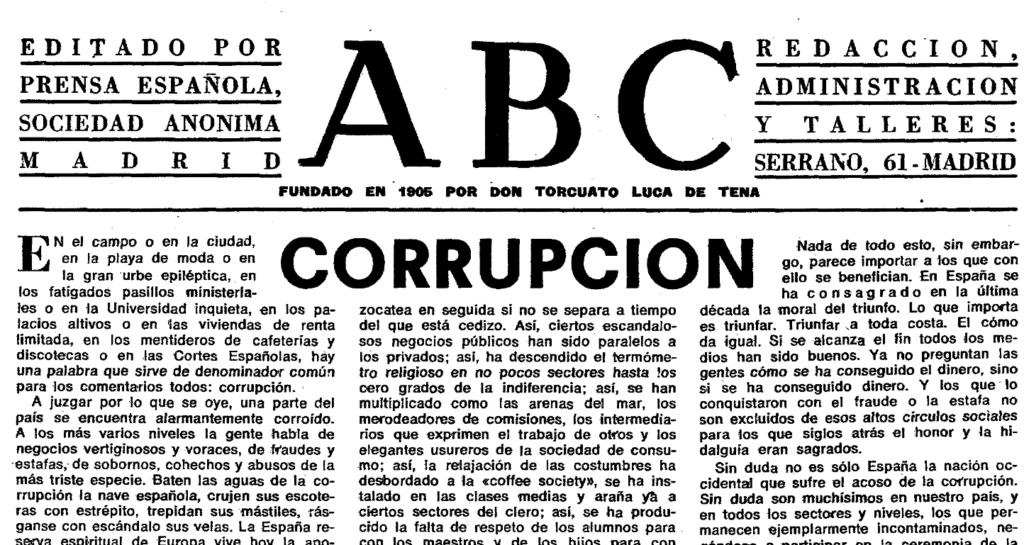

An increasing sense of perceived corruption marks the last years of the Francoist dictatorship. An editorial about corruption in ABC (Ansón, 1973), the monarchist and conservative newspaper, two years before the dictator’s death, gives a clue of the last years of Francoism (Fig. 82). Ansón blamed technocrats and the arrival of the television and linked it to the problems that developmentalism had brought, in contrast with the original values of Francoism. According to him, corruption invaded every sector of society. Another insight into how corruption was in the public debate is provided by the creation of an association to combat corruption by two layers in 1975 (ABC, 1975).

Transition and Democracy #

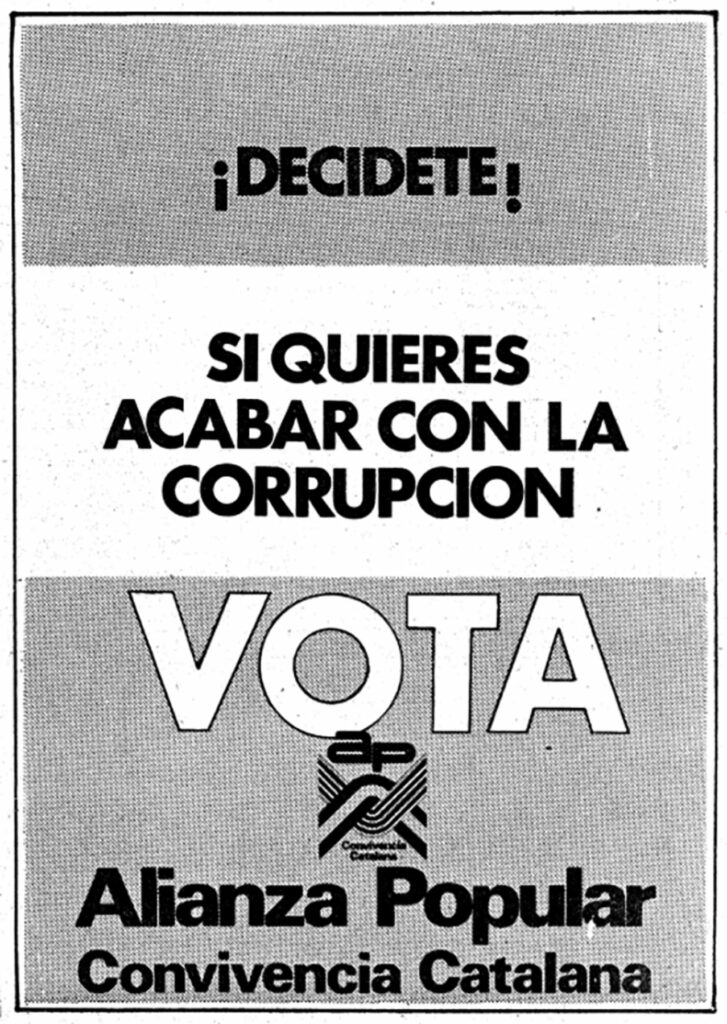

Franco’s death brought the hope of ending corruption as a systemic problem. Thanks to the arrival of transparency measures with democracy, it was expected to disappear, thus linking corruption to Francoism. Newspapers published many news stories and editorials about this, and the emergent political parties used it with political goals (Sánchez Sánchez & Rey-Mazón, 2019). Corruption was also present in the first electoral processes (Fig. 33).

After the approval of the democratic Constitution in 1978 and the arrival of the socialists to the government in 1982, a new period started. It was marked by solid economic growth (1985-1991 “cultura del pelotazo”) related to rezoning, privatization processes, and the construction of big infrastructures. The most important corruption scandals were related to construction, urban planning, and irregular financing of political parties at the national and regional levels. Some of them are directly related to the new wave of scandals that would be known in the 2000s (Gürtel), like the Naseiro scandal, which exposed PP’s illegal financing but was archived due to illegal wiretapping.

However, what marked this period under the PSOE government were the corruption scandals related to the socialists, like Guerra, GAL, Roldán, and Filesa, which exposed the illegal financing of the party. Those scandals made the socialists lose the elections in 1996. It is almost impossible to cite all scandals that surfaced in that period. However, the famous ones could be narrowed down to: AVE, Banesto, CESID, Expo’92, Fondos reservados, Hormaechea, KIO or PSV (extracted from Garzón (2015). Davesa and Palau (2013, p. 101) summarize this period very well and how El Mundo changed the media ecosystem in Spain:

“The media coverage of corruption scandals at the start of the 1990s clearly illustrates the strong connections between the media and political parties in Spain, and how political parallelism limits the role of the media as ‘watchdog’. At the end of the 1980s, the socialist party’s control of the media, the weakening of the main opposition party and a political context unfavourable to the publication of scandals that could threaten the consolidation of democracy, prevented political scandals from becoming too visible (Jiménez, 2004). But this scenario radically changed in the first half of the 1990s, above all with the founding of El Mundo in 1989, which together with Diario 16 launched a campaign aimed at uncovering political scandals (such as in the Filesa case, the GAL incident, the appropriation of public funds by Luis Roldán, tax evasion by the governor of the Central Bank, and the scandal of the CESID documents) as a strategy to destabilise the socialist government and help the opposition (Castells, 2009; Cabrera and del Rey, 2002; Canel and Sanders, 2006; Hallin and Mancini, 2004). This strategy was driven by political motives, but also served economic interests. Presented to the public as an independent newspaper, based on ‘investigative journalism’, and critical of a corrupt government, El Mundo succeeded in becoming the second most read newspaper in Spain: the year of its launch it had a circulation of 131,626 (Canel and Sanders, 2006:63)”.

Aznar and the economic boom (1996-2004) #

The electoral victory of the Peoples’ Party (PP) in 1996 ended 15 years of consecutive socialist governments and seemed to end a period of intense political corruption. The PP had based the bulk of its opposition strategy on this issue during a very tense legislature (1993-1996). Once in power, the perception of corruption dropped drastically, according to the CIS barometers.

During José María Aznar’s (PP) time in the government, there was significant economic growth, more pronounced than in other European economies, and a reduction in unemployment rates. At the same time, the privatization of state-owned companies continued, converting public into privatized monopolies, sometimes under control of friends of the president (e.g. Telefónica). In 1998, a new law (Ley 6/1998, de 13 de Abril, Sobre Régimen Del Suelo y Valoraciones, 1998) set the seed of the real estate and credit bubble and the many corruption scandals related to urban planning in municipal and regional governments (Jerez Darias et al., 2012).

This apparent period of low perceived corruption, together with the economic boom, concealed some important corruption scandals, like Forcem, Gescartera, Lino, Pallerols, Sanlúcar, Tabacalera, Villalonga and Zamora (Sánchez Sánchez & Rey-Mazón, 2019). According to the report published in 2001 by the then recently created Group of States against Corruption (GRECO), the Council of Europe’s anti-corruption monitoring body, the number of yearly corruption cases4 assigned to the ACPO (Special Attorney General’s Office for the Repression of Economic Offences related with Corruption) declined during the period 1996-2000 █▄▆▃▂ (1996, 47 cases; 1997, 23; 1998, 40; 1999, 20; and 2000, 13) (GRECO, 2001).

During those years, various important corruption schemes were taking place but were not noticed by the news media or the general public. It would not be until a decade later that they would come to public scrutiny and fill newspaper front pages. That is the case of the first steps of the Gürtel scandal, related to the illegal funding of the PP party, that started in the 1990s, but the news media did not publish it until 2009. There are other examples, like the illegal commissions of the 3% scandal related to CiU and Jordi Pujol, president of Catalonia until 2003, that were not publicly known until the 2010s.

GRECO, the Auken report and a new wave of scandals (2004-2019) #

In 2004 José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero won the elections and took back the office for the socialist party. Spain was already part of the GRECO, almost since its foundation in 1998, but it was not until 2005 that signed the Criminal Convention Against Corruption, and not until 2010 that it was ratified. However, one thing was to sign this list of recommendations and another to follow them. In 2011, 11 from 15 GRECO recommendations had not been followed. Both parties alternating in power, PP and PSOE, seemed not interested in applying measures to combat corruption.

In those years, corruption was strongly linked to urban planning and the construction industry, mainly on the coast and in big cities, but also small ones and villages. Different reasons contributed to this: (a) the before mentioned 1998 law gave municipalities the power to take decisions regarding urbanization development and rezoning; (b) lack of transparency and control by regional and state bodies; (c) the ongoing property bubble that fueled speculative operation for the benefit of the private sector (real estate and construction companies) (Villoria & Jiménez, 2012). Different publications and reports published during and after the property bubble crash account for this situation (Fernández Durán, 2006; Greenpeace España, 2013; Rey-Mazón & Lorenzo Montero, 2011).

In 2009, the European Parliament voted in favor of what was later known as the Auken report. A report was written by Margrete Auken, a Danish member of the European Parliament, that documented and criticized the extensive urbanization practices and endemic corruption in Spain that had profound environmental, social, and economic consequences (Auken, 2009):

“S. (…) every level of authority, from central to autonomous and local, has been responsible for setting in motion a model for unsustainable development that has had extremely serious environmental consequences, as well as economic and social repercussions,”

Among the 36 recommendations, we highlight two:

“2. Calls on the Spanish authorities to abolish all legal forms that encourage speculation, such as urbanisation agents; (…)

18. (…) the absence of clarity, precision and certainty with regard to individual property rights contained in existing legislation, and the lack of any proper and consistent application of environmental law, are the root cause of many problems related to urbanisation and that this, combined with a certain laxity in the judicial process, has not only compounded the problem but has also generated an endemic form of corruption of which, once again, the EU citizen is the primary victim, but which has also caused the Spanish State to suffer significant loss;”

This report built on top of previous resolutions on this subject that the European Parliament had already adopted in 2005 “on the alleged abuse of the Valencian Land Law” (Fourtou, 2005) and in 2007 “Fact-finding mission to the regions of Andalusia, Valencia and Madrid” (European Parliament, 2007). The places included in the titles provide clues to where speculation and corruption related to urbanization developments occurred.

During this period, under the socialist government (2004-2011), there was a long list of scandals that involved PP, PSOE, and CiU in regional and national Administrations: Campeón, Ciudad del Golf, ERE, ITV, Gürtel, Millet, Pretoria, to name a few.

In February 2009, the first news about the Gürtel scandal was published (Mercado, 2009), a case that the ACPO had investigated since 2007. This, together with other scandals, started a new wave of scandals and raised public concern about corruption in the following years. I highlight Gürtel case, that implicated officers of the Popular Party’s (PP) in bribery, tax evasion and money laundering activities, because is related to other scandals like the “Bárcenas papers” (Mercado et al., 2013). It dramatically changed people’s attention to corruption (see 6.2 Public perception of corruption in Spain). Despite this scandal, Mariano Rajoy won the general election, with the best results of PP ever, and was elected Prime Minister in December 2011. The socialist government was punished by the economic situation after the credit and property crisis.

The process of public indignation about political corruption was boosted by the 15M mobilization and several corruption cases that involved almost every institution in the country and arrived at its peak in 2014 (see various front pages about corruption as a general problem in figure 85). The major political parties (PP, PSOE, CiU), the Royal Family, the leading labor unions, the Supreme Court, the National Bank, and many saving banks were involved in important scandals that filled the news agenda for years: Gürtel, Noos, ERE, Pujol and family, Bankia, Palau-Millet, Púnica, Faisán, 3%, Cursos Formación, Rato, Master Cifuentes or Lezo are ones that occupied more spaces in the front pages in the 2009-2019 period (see Sec. 9.2 Fragmentation of the corruption agenda) (Rey-Mazón, 2022a).

The 15M-indignados movement that, since May 2011, with a solid critique of the structural problems of the bi-partisan system and the systemic corruption, changed the political environment. It is in part to be responsible for a new political cycle where other parties like Podemos, Ciudadanos, or VOX challenged the hegemony of the PP and PSOE.

In 2018, the first definitive court ruling of the Gürtel scandal convicted different PP officials. It ruled that the party benefited from the corruption scheme, recognizing that there was parallel financing and accounting structure since the 1990s. Mariano Rajoy lost a motion of no confidence5 brought by PSOE, the first one to be successful since the Transition.

Summary #

In conclusion, corruption scandals and corruption perception have been a constant characteristic during the past two centuries in Spain. They have been many times at the center of the political debate, making governments fall and forcing numerous resignations among elected officials. The construction of big infrastructures, organization of international events, and urban development have been the fields that corruption practices have used to take benefit, thanks to low levels of transparency and accountability, and a judiciary system and news media that have not always been successful in detecting and bring to public awareness the of the politicians and the economic elite. In short, in the history of corruption in Spain, corruption has been the center of the political debate since the 19th century and has played an essential role in critical moments of political life, being the leading cause of making two governments fall in the Second Republic, and two more recently in democracy.

1The six selected newspapers are the ones used in the case studies in chapter 9 and the ones included in the Color Corrupción database (Rey-Mazón, 2022a).

2There are also examples of printed news media that closed their printed editions and turned into only digital platforms, like Publico.es.

3For example the barometers of April 2009, April 2011, October 2019 and December 2019.

4These cases comprise both cases involving corruption and economic offenses. Data until 2000.10.23.

5On June 2017, Rajoy had already won an earlier no-confidence motion brought by Unidos Podemos party, as he we was due to appear as a witness in the the Gürtel trial in July.

Bibliography of this chapter #

ABC. (1975, April 22). Dos abogados promueven una asociación para luchar contra la corrupción. ABC.

AIMC, A. para la I. de medios de comunicación. (2021). Marco General de los medios en España 2021. https://www.aimc.es/a1mc-c0nt3nt/uploads/2021/02/marco2021.pdf

Ansón, L. M. (1973, November 17). Corrupción. ABC, 3.

Auken, M. (2009). Report on the impact of extensive urbanisation in Spain on individual rights of European citizens, on the environment and on the application of EU law, based upon petitions received. European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-6-2009-0082_EN.html

Baumgartner, F. R., & Chaqués-Bonafont, L. (2015). All News is Bad News: Newspaper Coverage of Political Parties in Spain. Political Communication, 32(2), 268–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.919974

Blasco-Duatis, M., Coenders Gallart, G., & Sáez, M. (2018). Compositional visualization of intermedia agenda setting by the main media groups and political parties in the Spanish 2015 General Elections (73rd ed.). Revista Latina de Comunicación Social. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2018-1255en

Brenan, G. (1950). The Spanish labyrinth: An account of the social and political background of the Civil War ([2d ed.]). University Press.

Broms, R., & Rothstein, B. (2020). Religion and Institutional Quality: Long-Term Effects of the Financial Systems in Protestantism and Islam. Comparative Politics, 52(3), 433–454. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041520X15714522654104

Brown, J., Pischke, O., & Beck, J. (2015). Building the factory. https://kijkonderzoek.nl/images/ Presentaties/150127%20Kan- tar%20Media.pdf

Cagenius, T., Fasbender, A., Hjelm, J., Horn, U., Ivars, I. M., & Selberg, N. (2006). Evolving the TV experience: Anytime, anywhere, any device. 83(3), 107–111.

Davesa, F., & Palau, A. M. (2013). The Impact of Media Coverage of Corruption on Spanish Public Opinion. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 144. http://reis.cis.es/REIS/PDF/REIS_144_05_ENGLISH1381482849627.pdf

European Parliament. (2007). Fact-finding mission to the regions of Andalusia, Valencia and Madrid. European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-6-2007-0281_EN.html

Fernández Durán, R. (2006). El tsunami urbanizador español y mundial: Sobre sus causas y repercusiones devastadoras, y la necesidad de prepararse para el previsible estallido de la burbuja inmobiliaria. In http://www.nodo50.org/ramonfd/tsunami_urbanizador.pdf. Barcelona : Virus Editorial, 2006. http://libros.metabiblioteca.org/jspui/display-item.jsp

Fernández Sebastián, J. (2008). Diccionario político y social del siglo XX español. Alianza. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=520374

Fourtou, J. (2005). Report on the alleged abuse of the Valencian Land Law known as the LRAU and its effect on European citizens (Petitions 609/2003, 732/2003, 985/2002, 1112/2002, 107/2004 and others). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-6-2005-0382_EN.html

Garzón, B. (2015). El fango: Cuarenta años de corrupción en España (1a ed). Debate.

GRECO. (2001). First Evaluation Round. Evaluation Report on Spain. Conseil de l’Europe. https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=09000016806c9cdc

Greenpeace España. (2013). Destrucción a toda costa 2013. Greenpeace España. http://www.greenpeace.org/espana/es/reports/Destruccion-a-toda-costa-2013/

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge University Press.

Ley 6/1998, de 13 de abril, sobre régimen del suelo y valoraciones, Pub. L. No. Ley 6/1998, BOE-A-1998-8788 12296 (1998). https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/1998/04/13/6

Jerez Darias, L. M., Martín Martín, V. O., & Pérez González, R. (2012). Aproximación a una geografía de la corrupción urbanística en España. Ería: Revista cuatrimestral de geografía, 87, 5–18.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1999). The quality of government. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 15(1), 222–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/15.1.222

López Villaverde, Á. L. (2013). El poder de la Iglesia en la España contemporánea. La llave de las almas y de las aulas. Libros de la Catarata.

Massot, J. (1994, April 20). Entrevista a Paul Preston, biógrafo de Franco. ’ Franco quiso entrar en la Segunda Guerra Mundial para rehacer las glorias imperiales’. La Vanguardia.

Mercado, F. (2009, February 6). Garzón desmantela una gran trama de corrupción política vinculada al PP. El País. https://elpais.com/diario/2009/02/07/espana/1233961201_850215.html

Mercado, F., Jiménez, M., Cué, C. E., & Romero, J. M. (2013, January 31). Las cuentas secretas de Bárcenas. El País. https://elpais.com/politica/2013/01/30/actualidad/1359583204_085918.html

Ognjanov, G., & Mitic, S. (2019). TV Audience Measurement in Europe: Do Advertisers Really Know What They are Paying for? Journal of Emerging Trends in Marketing and Management. http://www.etimm.ase.ro/?p=564

Parker, R. (2007, September 13). Focus: 360-degree commissioning. Broadcast. https://www.broadcastnow.co.uk/focus-360-degree-commissioning/121754.article

Rey-Mazón, P., & Lorenzo Montero, R. (2011). 6000km. Paisajes después de la batalla. Basurama. https://6000km.basurama.org/libro/ and https://issuu.com/basurama/docs/libro-6000km_1.2

Rodríguez Vázquez, A. I., García-Orosa, B., Portilla, I., & Direito-Rebollal, S. (2021). Capítulo 9. El panorama cambiante de los sistemas de medición de audiencias. Espejo de Monografías de Comunicación Social, 3, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.52495/c9.emcs.3.p73

Salaverría, R., Martínez-Costa, M. del P., Breiner, J. G., Bruna, S. N., Rey, M. C. N., & Jimeno, M. Á. (2021). Capítulo 1. El mapa de los cibermedios en España. Espejo de Monografías de Comunicación Social, 3, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.52495/c1.emcs.3.p73

Sánchez, P. (2017). La medición de audiencias en la encrucijada. Ipmark: Información de publicidad y marketing, 836, 70–73.

Sánchez Sánchez, I., & Rey-Mazón, P. (2019). C de España: Manual para entender la corrupción. Almud Ediciones de Castilla-La Mancha. https://colorcorrupcion.montera34.com/

Santiago, F. (2017). Fragmentación de la audiencia: Retos de la medición. https://www.aimc.es/a1mc-c0nt3nt/uploads/2017/09/170609_fsc_jornada_occ_barcelona-2.pdf

Uslaner, E. M., & Rothstein, B. (2016). The Historical Roots of Corruption: State Building, Economic Inequality, and Mass Education. Comparative Politics, 48(2), 227–248. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041516817037736

Vilanova Ribas, M., & Moreno Julià, X. (1992). Atlas de la evolución del analfabetismo en España de 1887 a 1981. Ministerio de Educación.

Villoria, M., & Jiménez, F. (2012). La corrupción en España (2004-2010): Datos, percepción y efectos / Corruption in Spain (2004-2010): Data, Perception and Consequences. Reis, 138, 109–134.

Woodberry, R. D. (2012). The Missionary Roots of Liberal Democracy. American Political Science Review, 106(2), 244–274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000093